It is no secret that engine manufacturers from around the globe have been actively working to develop and fine-tune more efficient engines that run on cleaner and more sustainable fuels. A significant fruit of that effort is the development and subsequent adoption of natural gas-powered engines for off-highway applications.

This shift to renewable energy represents a major opportunity for lubricant marketers, David Tsui, a project manager in consulting firm Kline & Co.’s Energy practice, said in an online webinar in late May. The opportunities are especially prevalent for marketers that have strong ties with original equipment manufacturers, he said.

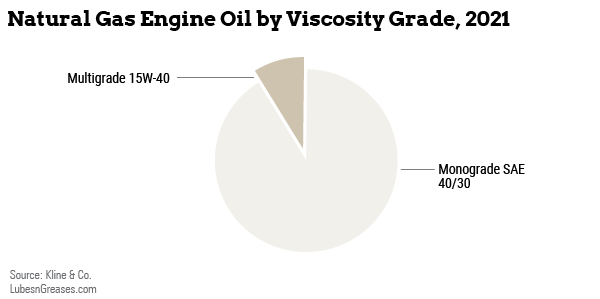

The webinar was centered around Kline’s study “Natural Gas Engine Oils: Global Market Analysis and Opportunities.” The study explored demand for natural gas engine oils in select markets around the world in non-transport applications and used 2021 as the base year. Such markets as oil and gas, power plant, pipeline, agriculture, and commercial and residential were included in the study. However, transport applications, like buses and trucks, ships and cars were excluded from the study.

How Clean Is Natural Gas?

What are the benefits of using natural gas as opposed to more traditional fuels, such as gasoline or diesel?

According to the U.S. Energy Information Administration, “Burning natural gas for energy results in fewer emissions of nearly all types of air pollutants and carbon dioxide than burning coal or petroleum products to produce an equal amount of energy. About 117 pounds of CO2 are produced per million British thermal units equivalent of natural gas compared with more than 200 pounds of CO2 per MMBtu of coal and more than 160 pounds per MMBtu of distillate fuel oil.”

Chevron’s website confirmed that “all natural gas engines deliver lower particulate matter emissions than diesel engines of comparable horsepower.”

How Are Natural Gas Engine Oils Different?

First and foremost, engines powered by natural gas create certain conditions that often cannot be handled by diesel or gasoline engine oils.

“One of the bigger opportunities is this focus on alternative gases or alternative fuels; be it ‘green’ hydrogen or other types of gaseous fuels, they’ll provide different combustion environments for the engine oils,” Tsui said. “So certainly there will be a need for different types of engine oil or customized or tailored engine oil for specific applications.”

But how exactly do natural gas engines differ from other internal combustion engines, and how do these differences force changes to the engine oil formulations that are used to lubricate them?

An article published by Machinery Lubrication stated that natural gas engines must be equipped to burn several different types of natural gases. These include sour gas, which contains sulfur; sweet gas, which contains zero sulfur and only a small amount of carbon dioxide; wet gas, which contains relatively high levels of component gases, like butane; as well as digester or landfill gas, which is made up mostly of methane and carbon dioxide and often contains such halogens as fluorine and chlorine.

According to Castrol, “natural gas engines have very similar engine oil requirements as diesel” engines. However, there are a few key differences that must be considered. For instance, “natural gas engines have higher combustion and operating temperatures,” the lube maker said. “Fuel combustion is more complete, and natural gas engines do not generate soot. The need for detergent and dispersant additives is significantly lower than with diesel engines.”

|

“Fuel combustion is more complete, and natural gas

engines do not generate soot. The need for detergent

and dispersant additives is significantly lower than

with diesel engines.”

– CASTROL |

However, pipeline-quality natural gas burns a bit differently than landfill gas. According to Chevron, landfill gas contains 40%-60% methane and is littered with considerable amounts of siloxanes and other contaminants. Because of this, the lubricants used in engines burning landfill gas must protect against higher levels of acid corrosion and will likely require higher additive levels to get the job done. In other words, the base number for engine oils used to lubricate landfill or sour gas-fueled engines is typically higher than that used in pipeline natural gas-powered engines.

The base number—commonly referred to as BN—is a measure of the alkalinity of an engine oil. According to Chevron, an oil’s alkaline reserve neutralizes acids generated during the fuel combustion process. “These acids aggressively attack metal surfaces,” the company said, “so it is very important to formulate engine oils with sufficient alkaline reserve to help prevent engine wear.”

Natural gas engine oils can achieve the desired BN by including a “combination of detergents, dispersants and antioxidants” in the formulation, Chevon said.

Natural gas engines operate at much higher temperatures than many other internal combustion engines. Due to these more demanding operating temperatures, oil oxidation and nitration stability are necessary characteristics of natural gas engine oils, too.

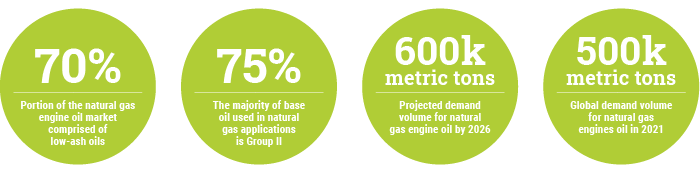

“Higher combustion temperatures in natural gas engines make exhaust valves more sensitive and prone to ash deposits,” Castrol added. “While this ash can help protect against valve recession, high-ash levels can create deposits that can lead to valve torching.” Because of this, natural gas engine oils are generally formulated to contain low amounts of ash. In fact, nearly 70% of the natural gas engine oil market is made up of low-ash oils.

Valve recession is the premature wearing of the valve seat into the cylinder head.

Of course, exhaust emissions from all types of internal combustion engines are now and will continue to be a serious concern. To control or even eliminate these emissions, some of the current natural gas engine designs are fitted with catalytic converters. This addition necessarily limits the types and amounts of additives that can be used in the lubricants. That is to say that combusted additives can leave behind ash, which can damage aftertreatment devices, such as exhaust catalysts.

Aside from the additives, an integral part of every engine oil formulation is the base stock. For natural gas engine oils, the base stock must be oxidatively stable.

In 2021, a few different base oil types were being used to formulate natural gas engine oils, but the overwhelming majority (75%) of base oil used in natural gas applications is Group II, according to Kline’s Tsui.

Group II has largely replaced Group I in natural gas engine oils. “Pricewise it has been fairly comparable to Group I because of diminishing supplies,” Tsui said. “There are some markets where Group I is quite readily available, so marketers still use it in some NGEO formulations.”

He added that “demand for Group III and above category base oils is significantly low compared to other base oil categories. Group III and above base oils are comparatively more expensive than the other base oils and thus have not been able to penetrate the market.”

Use of Group III base oils and synthetic base stocks—such as polyalphaolefins and esters—is currently small but growing, he added.

Growth Projected for Natural Gas Engine Oils

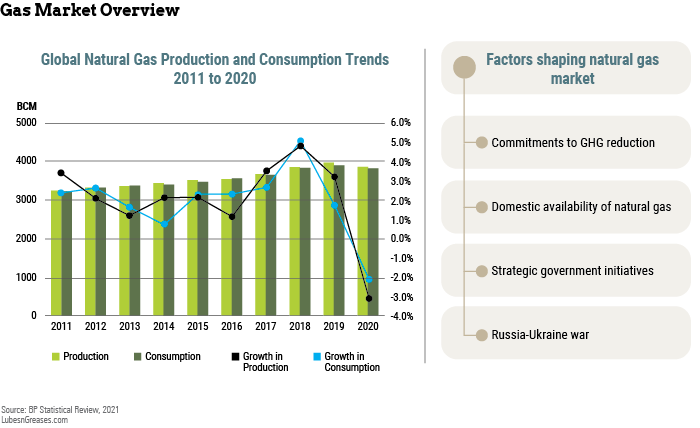

In the quest for cleaner energy, it stands to reason that the demand for natural gas would increase. In fact, global natural gas consumption generally grew up until 2020 when the COVID-19 pandemic struck and disrupted the previously expanding market.

Even as the effects of the pandemic waned, other disruptions to the natural gas market arose. Many question whether the Russian invasion of Ukraine and subsequent American and European sanctions on Russian energy products will tamp down demand for natural gas, and by how much. What’s more, many countries have implemented government policies to transition away from all fossil fuels—including natural gas—smothering demand even further.

“We do expect to see natural gas consumption recover and continue to grow,” Tsui said. “But growth rates will be slower than previous projections” because of these disruptions.

Kline & Co. projected that global demand for natural gas engine oils in non-transport applications will grow at a compound annual rate of 4% through 2026 and will surpass 600,000 metric tons, as the fight against climate change spurs the use of engines powered by natural gas.

Where is most of this natural gas engine oil demand coming from?

According to Tsui, North America accounted for more than half the estimated 500,000 tons of global natural gas engine oil demand last year. The United States by itself made up nearly half of last year’s global natural gas engine oil demand, the consultancy discovered. Following North America were Asia-Pacific and Europe.

Tsui explained that Asia-Pacific, namely China, has a lot more room for natural gas engine oil to grow, because the country consumes surprisingly little natural gas engine oil considering its installed power capacity.

“In China, they actually use a lot of converted diesel engines and convert diesel engines to natural gas use for power generation,” he said. However, the country has continued to use heavy-duty motor oil to lubricate these engines instead of natural gas engine oil.

“These are opportunities for lubricant marketers to show them why using a heavy-duty motor oil in an NGEO application isn’t really the proper, best way to get the most” out of their natural gas engines, he said.

Who’s Leading the Pack?

The top natural gas engine oil supplier in the 16 key countries covered in Kline’s study was ExxonMobil, followed by Shell, Chevron, Phillips 66, Citgo and Petro-Canada.

Why might some natural gas engine oil makers be selling more than others?

“OEM recommendations play a huge role in how these lubricant marketers stack up,” Tsui explained. This is often due to maintenance contracts during warranty periods, as these contracts generally call for servicing using only OEM-recommended fluids.

Sydney Moore is managing editor of Lubes’n’Greases magazine. Contact her at Sydney@LubesnGreases.com