In a finding that signals potential challenges for electric vehicles, a team of researchers from academia and industry observed that electrical charge applied to the interface of metal surfaces can significantly increase the rate of wear when they slide against each other.

Speaking Nov. 30 at the Tribology and Lubrication for E-Mobility Conference organized in San Antonio by the Society for Tribologists and Lubrication Engineers, Texas A&M University’s Ali Erdemir said the results are concerning because of the charges prevalent in EVs.

“The bottom line is that regardless of the fluid you actually tend to get more severe wear when the electricity is passing through, and the surface is a mess,” who was part of a research team that also included individuals from Afton Chemical Corp. and Tecnologico de Monterrey in Mexico.

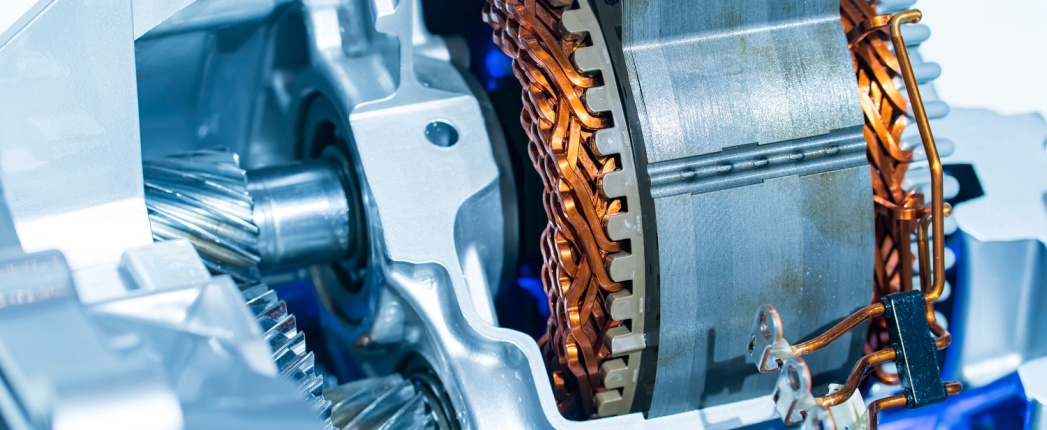

With sales of battery-powered vehicles and plug-in hybrids shooting up in many countries, the lubricant industry is scurrying to develop lubricants and fluids to protect them from wear and from the high levels of heat generated by EV batteries.

Erdemir said the team he was on ran tests on ball-on-disc tribometers that had been modified to apply a charge of 3 amps at the interface between the ball and disc. The group tested four fluids, some of which are commercially available. Erdemir said he did not know the base fluids with which they were made but that they had similar chemistries, similar levels of thermal conductivity, varying levels of electrical conductivity and kinematic viscosities that ranged from 18-30 square millimeters per second at 40 degrees C.

The fluids allowed significantly different amounts of wear when no charge was applied, Erdemir said, but the amount of wear jumped by a factor of between 2 and 5 when the electrical charge was applied. Wear increased even though electrification barely changed coefficients of friction, he added.

Erdemir said electrical charge also appeared to change the chemical reactions occurring at the interface. When no charge was applied, researchers found some matter on the surface post-test, mostly hematite, a hard iron oxide. Applying electricity lead to the formation of much more debris, mostly magnetite, which is less hard than hematite and significant amounts of carbon black.

Researchers heard a crying sound coming from the interface during the tests run with electrical charge, Erdemir said.

The interface “is clearly having a difficult time,” he said. “You not only have all these abrasive outside debris layers forming and potentially causing more severe abrasion and wear, but also you have this carbon generated and smeared on the surface.” He speculated that the carbon material may be repeatedly forming and getting removed and this dynamic may increase the amount of wear.

Erdemir said tests now need to be run on EV components and that the research team has begun doing this.

One audience member suggested that the 3 amps applied for this experiment may be significantly higher than those occurring in EVs. Erdemir said he has heard varying theories on the matter but that 3 amps is within the range of currents he has observed for other experiments involving EVs.

Another audience member speculated that the reaction to current could be due to the polarity of the fluids or to the presence of metal additives.