Accounting for Lubricants’ Positive Contributions to Sustainability

After years of work, lubricant industry trade groups adopted standards that marketers can use to calculate the carbon footprints of individual lube products – the amount of carbon dioxide generated in bringing a unit of engine oil, hydraulic fluid or grease to market.

These are considered among the industry’s most important contributions yet toward the sustainability movement, providing a crucial common language and means to measure, show and compare the sustainability of products. There is consensus among industry insiders that real progress toward making the industry more sustainable would not be possible without such tools.

But the work is not over, and one particular job looms large: how to define the effect a lubricant’s performance has on CO2 emissions during the use phasae. Those working on sustainability standards say this is another significant consideration in the overall effort to combat global warming. Moreover, they contend, it’s an opportunity for the industry and individual companies to receive credit for very real benefits reaped by end users and society in general.

“What we should be focusing on is calculating the use phase in whatever way possible,” Vasileios Bakolas, a principal expert in bearings research and development at Schaeffler Technologies AG and Co., said during a sustainability roundtable discussion on May 20 at the Society of Tribologists and Lubrication Engineers Annual Conference and Exhibition in Atlanta. “We have to find a way to include incorporate it.”

The difficulty is devising a practical way of accounting for such benefits when impacts can vary greatly not only from product to product – from one passenger car engine oil to another – but also from application to application – from the impact of a rolling oil in one hot aluminum rolling mill to the same oil’s use in another aluminum mill, or a copper mill.

Industry insiders say this task could require more work than the development of product carbon footprint standards and could take more than two years to accomplish.

Measuring Emissions Generated by Supplying Products

Over the past couple years, industry associations have adopted standards for calculation of lubricant product carbon footprints. In 2023 the American Petroleum Institute published a methodology and best practice for calculating carbon footprints of finished lubricants and conducting life cycle assessments of the same. In 2024 the Union of the European Lubricants Industry and the Technical Association of the European Lubricants Industry published a PCF methodology that they had developed jointly.

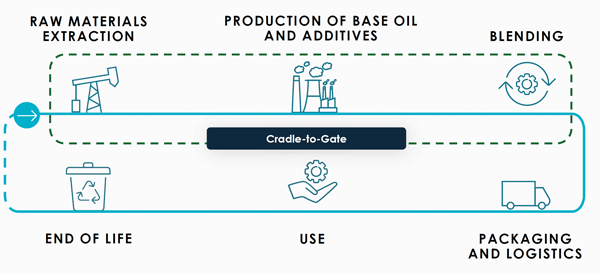

Each of these standards covers cradle to gate phases of the supply chain including: exploration and procurement of crude oil and other base raw materials; refining and other processing of those raw materials; transportation of feedstock, raw materials and finished product; and lubricant manufacturing and other operations of the marketer. The API standard also accounts for emissions generated by the collection and disposal of the lubricant. This is referred to as cradle to grave.

The methods use a combination of standardized and individualized data. The associations have provided estimated averages of emissions generated in the supply of base oils and additives, obtained in cooperation with suppliers of those materials. They also guide lube marketers in how to estimate emissions generated by their own operations – manufacturing and otherwise.

Raw materials account for most of the product carbon footprint of finished lubricants, according to Oskar Voegler, lubricants project manager for Carbon Minds GmbH, of Koln, Germany, who also participated in the roundtable. At least 58% of CO2 generated stems from the supply of base oils, depending on formulation and source proximity, while additives are responsible for up to 40%, depending on formulation and additives used. Blending accounts for only 1%.

What’s missing so far is the use phase of lubricants. Unlike other phases, which generate CO2 emissions, this one can head them off. The main way in which lubricants help avoid CO2 is by providing lubricity and reducing friction, helping to reduce energy consumption. Whether it comes from fuels or electricity, reducing energy consumption directly affects CO2 generation. But lubes also help in other ways. Preventing wear prolongs equipment life, reducing the need to build equipment and consumption of materials from which it is made. Insofar that CO2 is generated in the supply of virtually all materials, prolonging equipment life avoids new CO2 generation.

However, the amount of information needed to account for those benefits could be many times greater than the amount needed to for the carbon footprint methods developed to date. Again, that’s because many lubricants are used in numerous versions of equipment – different brands and models of passenger cars and heavy-duty trucks for automotive engine oils, different brands and models of refrigerators, or blow-molding machines or lathes and drill presses for compressor oils, hydraulic fluids or metalworking fluids, respectively. Some machines used in factory settings are customized and unique.

Speakers at the STLE roundtable agreed that CO2 avoidance in different equipment can be large enough to matter. One of those speakers, Ergon Sales Manager and Sustainability Lead Inga Herrmann, a member of the UEIL-ATIEL joint committee on sustainability, said the industry should determine impacts in different applications.

Stephan Baumgaertel, who has participated in and observed sustainability standard development efforts as managing director of Verband Schmierstoff-Industrie e.V., the German Lubricant Industry Association, opined that it is not practical to calculate in-use CO2 emissions impacts for the many applications of individual products.

Figure 1. Life Cycle Inventory

What does a PCF of a finished lubricant look like?

“If you try to account for the differences between different applications, you will have so many different circumstances to take into account,” he said on the sidelines of the roundtable discussion at STLE’s Atlanta conference. “You could never do all of this work.” A better approach, he suggested, would be to choose average or typical numbers that could serve as standard savings for categories of products.

Bakolas sounded at least somewhat in agreement with Baumgaertel. “There is a real challenge with avoided emissions because of the vast number of applications and the differences between them,” he said. “I think the solution is standardization.”

Equipment-specific Calculations

Herrmann said such an approach lacks the accuracy and validity of calculating specific products in specific applications. The way to obtain specific and reliable information, she contended, is to gather data from real field applications using – apparently on fuel or electricity consumption, which could be correlated to CO2 emissions. There might be arrangements to share information – thereby reducing the amount that needs to be gathered. The amount of information required would still be remarkably massive, but the gathering would be done by lubricant suppliers in cooperation with end-users – both of which would be motivated to show the emissions reduction.

“For us, ensuring credible and verifiable PCFs means moving beyond average assumptions and investing in robust data collection across our value chain,” Herrmann said. “Only then can we provide the level of transparency that regulators, customers, and our own sustainability goals demand. Therefore, our strategy is to help members understand the process and requirements, enable them with tools and work towards public data sources that enable harmonized rough assessments, if the data availability is not yet perfect for a member company.”

Speakers at the sustainability roundtable estimated it would take two to three years of diligent work on such a campaign before significant numbers of lube marketers could begin to factor in-use emissions reduction into PCFs in ways that are recognized as valid by government agencies or certifying organization.

EU Sustainability Policies of Interest for American Firms?

The European Union has by most measure been the world’s most proactive government in pushing the sustainability movement. A gap with the policies of the United States always existed, but it is growing during the second administration of American President Donald Trump, who is working to undo much legislation aimed at reducing greenhouse gas emissions.

Neverthelesss, an insider at the heart of European efforts to make lubricants more sustainable said there is still good reason for U.S. lubricant companies to remain tuned into the goings-on across the pond – and even to stay in step with it.

The EU is making a blueprint for the rest of the world,” Ergon Sales Manager and Sustainability Lead Inga Herrmann said during a May 20 presentation at the Society of Tribologists and Lubrication Engineers annual meeting and exhibition in Atlanta. “So it makes sense for U.S. companies to adhere to requirements if they wish to do business in Europe or eventually in other markets.”

Herrmann cited a number of EU sustainability policies affecting lubricants. The Carbon Border Adjustment Mechanism, which is being phased in by 2026, implements a tax on imported products with high carbon footprints. In the lubricants industry this means increased costs for products with base stocks or additives derived from petroleum.

The Ecodesign for Sustainable Products Regulation and the Digital Product Passport financially incentivize products that promote durability, that reduce carbon dioxide generation and that advance more sustainable end-of-life handling. The Central Securities Depositories Regulation requires increased transparency about supply chains and CO2 generated to bring products to market.

All of these policies create an environment that financially incentivizes businesses to be more sustainable, Herrmann said. “This means sustainability is no longer a trend. It is a business imperative.”

Trump is pushing back hard on such policies. In the U.S. he is working to eliminate regulations of air emissions and other pollution. He has also criticized other nations for adopting sustainable policies and pressured some to undo them.

Herrmann expressed confidence that this is a temporary trend for the U.S., predicting its government will reinstate pro-sustainability policies after Trump leaves office. “It will be on a slower pace for the next three years, but it won’t go away,” she said.

She acknowledged the recent rise of some sentiment in Europe that EU had become too aggressive about sustainability – that some of the main policies adopted would damage business and overly drain resources.

“I think we have to be careful that we are not overly aggressive,” she said. But she also predicted that the region will maintain a fundamental commitment to work toward climate change goals and promote other aspects of sustainability. Such commitments, she said, will create requirements for local companies and foreign ones wanting to do business there.

“Non-compliant products will not enter the EU market,” she said, “So this impacts businesses in Asia-Pacific, North America and other regions.”

Tim Sullivan is executive editor for Lubes’n’Greases. Contact him at Tim@LubesnGreases.com.