The pace of electric vehicle sales may be slowing — at least by some measures — but work to improve EV fluids and lubricants is accelerating.

The lubricants industry is working on the next generation of electric driveline fluids and is scurrying to accommodate automaker demands for performance jumps in a number of parameters, including copper compatibility, copper protection, protection from wear and operational efficiency, among — all fundamental to the viability of EVs.

With so many targets, formulators and researchers say it may be necessary to find balance between different goals.

Losing Sales Momentum

Worldwide EV sales are still growing fast, but the rate of increase has decreased the past several years. In 2025, combined sales of plug-in hybrid cars and those powered solely by battery reached 20.7 million, accounting for about 22% of all light-duty vehicle sales. The EV sales number for 2025 represented a 19% jump from 2024, a rate many industries would gush over, but for EVs it marked the fifth consecutive year that the rate declined, after jumps of 117% in 2021, 55% in 2022, 36% in 2023 and 27% in 2024.

The trend is expected to continue. Benchmark Market Intelligence forecasts growth of 16% in 2026, to 23.9 million. Analysts describe this year and 2025 as a stall, driven by a tail-off of growth in China, by far the largest EV market, and the United States, where an end to federal government subsidies has caused EV sales to fall. Still, most analysts predict global sales will continue climbing steadily. S&P Global’s forecast in 2024 was that BEV and PHEV sales will reach 70 million by 2035.

“Despite what the news says, we’re all very big on our electrification projects,” Afton Chemical R&D Director Chris Cleveland said Nov. 19 in Troy, Michigan, U.S., at the Tribology and Lubrication for E-mobility Conference organized by the Society of Tribologists and Lubrication Engineers. “I think this is what life will be like for the next five to 10 years.”

Cleveland couched the work going on now as the second generation of electric driveline fluids. From the early 2000s to around 2015, he said, hybrids and BEVs were just lubricated with automatic transmission fluids purposed for them. Then from 2015 to 2023, EV manufacturers employed the first generation of electric transmission fluids, which made a first step in efficiency and provided automatic transmission style protection for gears and bearings.

Fluids from both of these periods were based on milder chemistry so as to be compatible with first-generation materials in the motor and transmission. The result, Cleveland said, was compromises in performance.

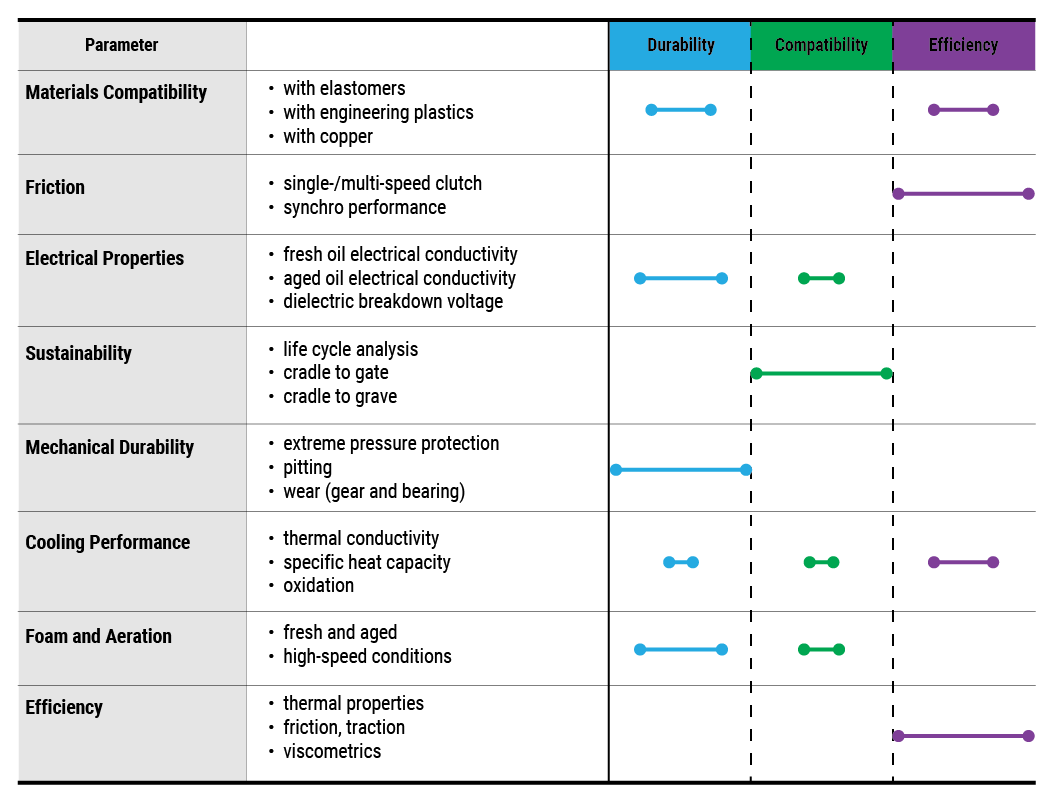

Since 2023, EV manufacturers have been pushing for a new generation of driveline fluids for architectures using a single fluid lubricates and cools the transmission and e-axle. The main goals (see Figure 1) include a significant step in efficiency in order to extend the range that can be driven on a single charge; a big step in mechanical performance, meaning more protection for components; focus once again on clutch friction performance. The wish list also includes improved sustainability; electrical properties that are more compatible with electrified vehicles; better cooling performance; and foam and aeration control.

Figure 1. Focus for the New Generation Electric Driveline Fluid

Copper Compatibility vs. Copper Protection

Because they generate force through electromagnetism, electric motors can deliver higher torques and do so from a standstill, compared with internal combustion engines, which must achieve higher revolutions per minute to reach high torque. Electric motors, therefore require enhanced extreme pressure protection, Cleveland said, adding that there is a common approach for accomplishing this.

“The EP performance of fluids improves with increasing levels of EP agents,” he said. The industry’s long-time standbys for EP performance have been derivatives of sulfur and phosphorus. The problem for electric motors is that they contain much more copper than internal combustion engines — chiefly the copper windings wound around the stator to create the electromagnetic field.

Much but not all of this copper is wrapped in insulation and lacquered to prevent contact with the driveline fluid, but insulation and lacquer crack and fall away over time, exposing the copper to the fluid. This leads to buildups of copper sulfide that form contact bridges between phases, causing short circuits and high temperatures that accelerate decomposition.

Peter Bjorkund, of Swedish truck maker Traton AB, said electric motors in heavy-duty vehicles face the same issue. He recounted a case study of stators from five buses in Sweden, Norway and Spain, four of which had electrical issues. Traton checked for copper damage and found significant variation — from mild discoloration of end windings to one case where large chunks of copper had disappeared.

Suspecting links to EP additives, Traton also measured sulfur and phosphorus levels in the driveline fluids from each bus. These levels varied, too, but the oil from the bus with the severely damaged windings had by far the highest levels of both elements, leading Traton to blame the higher levels of EP additives. For dramatic effect Bjorklund showed a photo of the highly damaged stator, but he added that this was a red herring. “Most likely it was topped off with oil containing EP additives,” he said.

Several speakers agreed that use of extreme pressure additives needs to be limited and that copper protection needs to be balanced with copper compatibility. Cleveland said the industry also needs to re-examine how it tests for copper compatibility. The most common method, he said, is ASTM D130, where copper tests are submerged in fluid at 150 degrees Celsius for three hours and visually examined for discoloration.

A better test for EV driveline fluids, he said, would run current through the copper, extend the timing of the test and add inductively coupled plasma analysis to measure for copper corrosion in both the vapor and liquid phases.

“If mechanical protection is preferred, is a passivating tarnish acceptable?” he asked. “Furthermore, if electrical hardware is insulated, can more durability-enhancing components be used?”

Improving Durability

Original equipment manufacturers are also looking for improved wear protection for hardware such as gears and axle bearings, but there the methodology is different. Speakers at the STLE meeting cited aeration as a contributor to hardware wear — more so than in internal combustion engines. The problem is that electric motors run at much higher speeds — greater than 20,000 revolutions per minute compared with mostly 2,000 rpm-4,000 rpm in ICEs.

This causes churning and aeration, which can trigger a range of problems including changes in viscosity that risk accelerated wear; reductions in temperature control resulting in excessive heating; and oxidation that speeds fluid degradation.

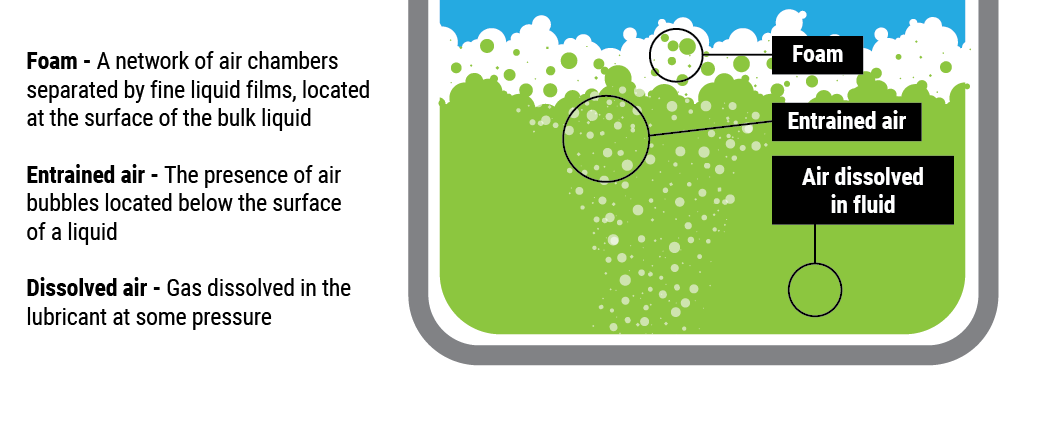

The industry’s combating of aeration has long focused on foaming and use of anti-foam agents or defoamers. Foam is a network of air chambers separated by fine liquid film that usually forms on the surface of bulk liquid. Defoamers are small, insoluble polymeric droplets, created during the lubricant or fluid blending process, which then exist throughout the fluid including in the film between foam air chambers. Droplets in the films deform them, causing the films to stretch until they rupture, releasing air.

This focus and approach can be inadequate in EVs, a Lubrizol official told the STLE e-mobility conference. It’s not just that electric motors amplify the level of aeration; Senior Scientist Greg Hunt explained that aeration can also take other forms with which defoamers may not help. Besides foam, mechanical churning also causes entrained air — air bubbles that form beneath the fluid surface — as well as dissolved air, where gas dissolved into the fluid at some pressure. (See Figure 2.)

Figure 2. Forms of Aeration

“Antifoams can actually make these other aspects of aeration worse,” Hunt said. Antifoam droplets on entrained air bubbles can form a “stagnant cap,” he said, which interferes with their rise to the surface, thereby slowing the air release rate.

A number of other factors also appear to affect aeration levels and the resolution of that aeration, Hunt said. Most lubricant additive packages include surfactant chemistry, which generally slows flow out of fluid films. This stabilizes foam and entrained air — the opposite of what is wanted. Similarly, some additive packages contain colloidally stable nanoparticles, which in degraded oil can absorb into the air-fluid interface, again stabilizing foam and entrained air. Fluids of lower viscosity enable more entrained air. Driveline fluid sumps in EVs are smaller than those for internal combustion engine oils, allowing less dwell time and less time for air or foam release.

Hunt contended the industry needs to gain a better understanding of aeration before it can properly address these needs.

“What should we care about?” he said. “Entrained air in the turbulent phase? Air release rate? Foam control?” He added that new tests are also needed since most existing aeration methods focus on foam. “Air entrained is a vital parameter to understand but often overlooked.”

Stretching Efficiency

Automakers are pushing hard for better efficiency in electric driveline fluids as a way to extend driving range. In this sense efficiency means reduced traction and friction, reduced churning losses and more effective heat management. Less friction and less energy lost to churning means more energy left to propel the vehicle. Optimizing temperature allows vehicle batteries to maximize their output. It also optimizes operation of units such as the oil pump and avoids thermal throttling, which actively lowers energy supply to the driveline when the vehicle starts to overheat.

Cleveland discussed tests that Afton conducted to compare the cooling and friction reduction capabilities of several categories of base stocks: Group III; two types of synthetics, which were polyalphaolefins and a second derived from plant sources; more linear synthetics, which were metallocene PAO and a low-traction variety of the plant-based stock; and a PAO-Group III blend.

The idea behind those choices was to test whether stocks with more uniform and linear molecular structure tend to have more cooling capacity and to reduce traction friction. The chemical production processes for PAO and plant-based synthetics allow particular molecules to be made with near complete uniformity, in contrast to Group III mineral oils that contain mostly straight hydrocarbon chains but also ringed and more branches molecules.

Afton compared cooling capacity using a closed-loop heat exchanger that pumped fluids originating at 90 degrees C through 9.25 feet of quarter-inch tubing. (See Figure 3.) This test included two viscosity grades of each category — 4.5 centiStoke and 5.5 cSt. The results were generally as expected. The linear synthetics outperformed the less-linear PAO and plant-based synthetic, which were close to equivalent to the PAO-Group III blend, which outperformed the straight Group III. The low-traction, linear plant-based synthetic scored best and cooled 8% better than the Group III, Cleveland said. He added that the 4.5 cSt varieties performed about 2.5% better than their 5.5 cSt counterparts, regardless of type.

Figure 3. Comparing Cooling Performance

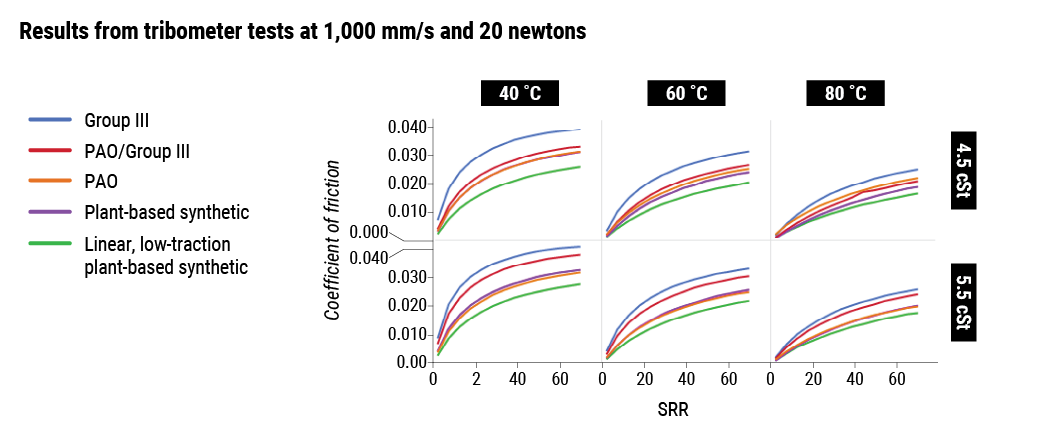

Friction coefficients were compared using a bench test applying 20 newtons of pressure at 1,000 millimeters per second, run at three different temperatures — 40 degrees, 60 degrees and 80 degrees. Overall, the low-traction plant-based synthetic performed best, followed by PAO, the other plant-based synthetic and Group III.

EV manufacturers have stated quite publicly the past couple years that they would like to find new types of base stocks that can help improve efficiency in EVs. Cleveland suggested the low-traction plant-based synthetic could offer the most promise out of those included in Afton’s study. Others are pursuing other materials. The International Colloquium on Tribology in Ostfildern, Germany’s Technische Akademie Esslingen in late January, included two presentations about research into the use of water-based lubricants as EV driveline fluids.

Figure 4. Fluid Friction/Traction Properties of Various Base Stocks

Both concluded that these fluids reduce friction better than conventional transmission fluids but are less effective at forming lubricating films or preventing wear. Still, researchers from Imperial College London, gear manufacturer SKF and an unnamed lubricant marketer — the partnership behind one of the presentations — believe water-based lubricants deserve more study said Imperial doctoral candidate Haochen Yao.

Significant work remains in numerous areas in the search for the next generation of electric vehicle driveline fluids. Lube formulators and researchers seem to embrace the challenge and are racing to find solutions.

Tim Sullivan is Executive Editor of Lubes’n’Greases. Contact him at Tim@LubesnGreases.com