The sustainability movement is viewed as a big opportunity for businesses offering biolubricants — a stimulator of government policy and business and consumer sentiment favoring products made of materials that come from plant and animal sources. All in the interest of combatting global warming and protecting human health and the environment.

The movement seems to be having the expected effect: The growth rate of demand for biolubricants has outpaced demand for all lubes for the past few years and is projected to continue doing so in years to come.

In some cases, though, other factors are helping the cause of biolubes. Italy is one of the hottest markets for this hot category of products, sporting one of the highest growth rates in demand for biolubes as well as a relatively high existing penetration rate. The reasons, though, have less to do with sustainability — although the movement has strong in Italy — than with tax policy that has long leant on petroleum products to raise money for government.

Marco Bellini, CEO of Milan-based Bellini S.p.A, summarized the situation in October in Stresa, Italy, at the annual meeting of UEIL, the Union of the European Lubricants Industry. “The Italian government unintentionally triggered a virtuous process of innovation: biolubricants.” Bellini supplies biolubes and other types of lubricants.

Italy is one of the largest economies in the European Union, ranking third after Germany and France and accounting for 12% of the bloc’s gross economic output according to an April estimate by the International Monetary Fund. Predictably then, it is also one of the largest EU lubricant markets. Demand in 2024 totaled around 380,000 metric tons, Bellini said, down from a peak of around 440,000 tons in 2021and back to approximately the same level as in 2015.

Italy has a large manufacturing sector — second largest in the EU after Germany and approximately the same size as France — so its industrial lubricants segment is relatively large, constituting half of the overall market at approximately 190,000 tons. The industrial segment has steadily declined since 2021, when it accounted for more than 250,000 tons, Bellini said, citing data from the Group of Industrial Lubrication Companies, or GAIL, on whose board of directors he sits. The automotive segment, in contrast, has been recovering from a COVID-19 pandemic low of 170,000 tons in 2020 and is nearly back to pre-covid levels of 200,000 tons.

Hydraulic oils are the biggest product category in the industrial segment, accounting for 31%. Metalworking fluids follow with a 20% share, followed by process oils and general industrial lubricants with about 15% each. That breakdown is roughly typical except that the portion for metalworking fluids is higher than in most countries.

“Yes, the amount of metalworking fluids is high,” Bellini said. “But this is consistent with Italy’s industrial profile, where metal processing, machining and mechanical engineering represent a major part of the manufacturing base.”

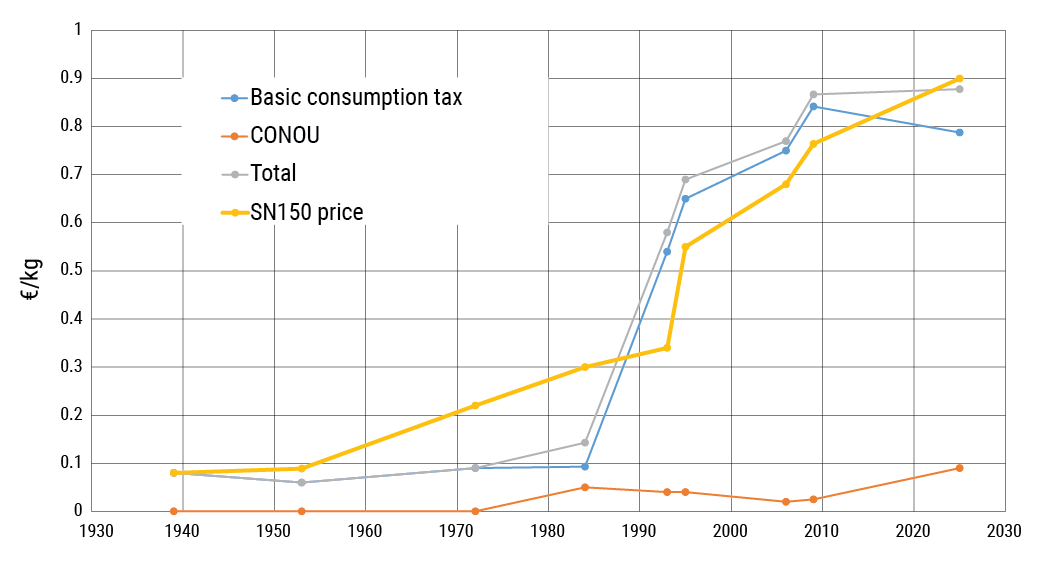

Bellini gave a history lesson dating to before World War II on Italian taxes that have impacted lubricants. In 1939, he said, the national government imposed a manufacturing tax equivalent to €0.08 per kilogram on mineral lubricants. A 1953 law changed that rate to €0.046/kg.

In the 1970s, a broad tax reform shifted taxes on petroleum products, including lubricants, from a production to consumption basis. The tax on mineral lubricants was set at €0.09/kg. In 1993 that rate was jacked up six-fold to €0.54/kg. Two years later it was raised again to €0.75/kg, and today it is €0.78781/kg.

This consumption tax is the biggest but not the only national tax on mineral lubes. In the early 1980s the government set a goal for all used lubricants in Italy to be collected and rerefined back into base oil, and to help cover costs it imposed a tax referred to by the non-profit organization that administers the program, the National Consortium on Used Oil, or CONOU. That levy has risen to €.08999/kg.

The total tax is quite significant, Bellini observed. (See Figure 1.) Since the early 1990s, it has usually exceeded costs of API Group I solvent neutral 150 base oil. With base oil prices having risen since 2010, SN150 now costs slightly more at €0.9/kg.

Figure 1. Italian Taxes on Mineral Lubricants, Cost of Base Oil

Though applied to finished lubricants, these taxes are charged only in proportion to the amount of mineral oil in the finished product. Bellini offered examples of three products. The first was an ISO 32 hydraulic oil that was 98% SN150, 1% viscosity index improver and 1% chemical additive package. It would be taxed at the full rate of €0.8778/kg. The second was a metalworking fluid made with 65% SN150, 15% sulfurized ester, 15% ester and 5% antioxidants. Because the latter three ingredients do not contain mineral oil, the tax would apply only to the SN150 content, making the rate €0.57/kg. The final product, a biobased hydraulic oil, contained 98% trimethylolpropane trioleate for base stock, 1% antiwear additives and 1% antioxidants. Because it has no mineral oil, the tax on it is zero.

The implication is obvious, Bellini said: a significant cost incentive for using lubricants that do not contain mineral oils, or at least more incentive than there would be without the mineral oil tax. He did not offer price comparison between the finished products, but a brief internet search suggests bulk prices for trimethylolpropane trioleate can range from €1,300/t-€3,900/t. That’s higher than costs for SN150, but factoring the mineral lubricant taxes brings base stock costs to the same neighborhood.

The mineral oil tax has encouraged Italy to use biolubricants at higher rates than most other countries, Bellini said. He cited a 2024 Kline report that estimated penetration of biolubricants in selected markets. (See Figure 2.) Italian demand for the category was 17,000 tons in 2024, Kline estimated, meaning market penetration of 3.3%. That was well behind Germany, the Nordic countries and Canada, which had rates of 7.8%, 6.5% and 4.7%, respectively, but Italy was close to even with South Korea and ahead of the United Kingdom, France, the United States, Brazil, Australia Indonesia and China.

Figure 2. Biolubricants Market Penetration

By select country, 2024

| Market | Penetration |

|---|---|

Nordics | 6.5% |

Canada | 4.7% |

South Korea | 3.4% |

Italy | 3.3% |

UK | 3.0% |

France | 2.9% |

United States | 2.5% |

Brazil | 2.0% |

Austraila | 1.4% |

Indonesia | 0.5% |

China | 0.2% |

Germany | 7.8% |

The same report estimated that biolubricant sales in Italy were growing at a cumulative annual rate approaching 5%, easily out-pacing all of these countries except China, which is growing from a much smaller base. (Figure 3) In March a Kline official estimated global biolubricant demand to be 400,000 t/y and forecast that the amount would increase at a cumulative annual rate of 4% through 2028. The firm predicts that total global lube demand will grow at a rate of just 0.5% over that period.

Figure 3. Biolubricant Growth Outlook

Versus overall market, forecast 2024-2034, select countries

“The tax has definitely encouraged the adoption of biolubricants, but the impact has not been dramatic,” Bellini said. “Growth is strong, and penetration is good but far from markets like Germany, which have regulatory obligations for biodegradables in certain applications. In Italy there is no regulation requiring biodegradable lubricants, so the penetration rate [for biolubes] is driven purely by market sensitivity, cost-competitiveness created by the tax, and voluntary choices in industry.”

The mineral lube tax has obviously been a cost for Italian consumers of lubricants made with conventional base stocks. Bellini nevertheless called it positive, and his explanation reflects the pro-sustainability sentiment that has held sway in the EU.

“Structurally, the tax is reasonable,” he said. “It supports sustainability by making mineral-oil-based lubricants more expensive. It is not overly burdensome for producers exporting abroad. It has helped develop a strong bio-lubricant ecosystem in Italy, even without regulatory mandates.”

And it has done so despite not really being designed to accomplish any of those things.

European Union Regulation: Adding Economic Consideration

The European Union has the world’s most ambitious policies combatting global warming and the strictest chemical safety laws, so it’s no surprise that it is grappling hardest with the effects of such regulations.

Giant cornerstone initiatives such as the Registration, Evaluation and Authorisation of Chemicals regulation and the European Green Deal have drawn complaints since their implementation — from 2006-2015 for REACH and 2020 for the Green Deal. Critics called REACH too expensive in terms of testing and recordkeeping requirements and chemical restrictions. The long list of policies under the Green Deal have drawn protests against things such as carbon taxes, low-emissions zones, wind farms, coal plant closings and climate-friendly standards for heating systems, in addition to over-arching complaints of changing too much too fast.

Objections ramped up the past couple years as economic output across the region sagged and several countries flirted with recession. At October’s Annual Congress of the Union of the European Lubricants Industry, the organization’s president, Mattia Adani, warned Europe faces an “impossible trilemma” — increasing difficulty to maintain its high social and environmental standards and commitment to free trade while keeping its industry competitive.

EU leaders have responded by easing some rules, which has drawn criticism from supporters of the previously policies. Overall, however, they so far are not giving up on their environmental of safety goals, instead couching some as economically strategic and increasing support for business. Adani cited these initiatives that stand to impact the lubricants industry.

Automotive Package: In December the European Commission proposed a set of rules aimed at easing emissions reduction targets and giving automakers more flexibility to meet them. The existing target of reducing 2021 levels of emissions by passenger cars by 100% by 2035 would be reduced to 90%, and automakers could continue selling plug-in hybrids, range-extender vehicles, mild hybrids and even cars powered only by internal combustion engines if they used low-carbon steel and biofuels.

The package also includes support for EVs, such as subsidies for purchases of models built in the EU; mandates for corporate fleets to shift to BEVs; a new category of vehicles for small, affordable EVs; support for charging infrastructure; and financial and policy support for the development of a battery supply chain in Europe. It would also aim to reduce red tape for the industry.

The package still needs adoption by the European Parliament, and negotiation with member states is expected to take the first half of 2026.

Table 1. European Union Policy Revisions

Recent or underway

| Initiative | Key Points | Status |

|---|---|---|

Sustainability Reporting Omnibus | Eases sustainability reporting requirements | Adopted by EC, needs EP approval |

REACH Revision | • Reaffirms safety commitment • Simplify rules • Practical PFAS considerations | EC drafting proposal |

Automotive Package | • Slightly eases emissions targets • Technological flexibility • Supports EU industry | European Commission proposal awaiting European Parliament approval, possibly mid-2026 |

Chemical Industry Package | • Support for threatened EU sectors • Support for sustainable chemicals | EC developing. Implementation during 2026 |

Bioeconomy Package | Supports investment and innovation in biomass conversion to food, materials, energy | Implemented in November |

Circular Economy Act | Aims to double recycling by 2030 | Adoption scheduled early 2026 |

Motor Vehicle Block Exemption Regulation Evaluation | Not yet determined | Potential amendment in early 2026 |

Sustainability Reporting Omnibus: In December the parliament adopted a package that eliminates sustainability reporting requirements for companies with less than 1,000 employees; protects smaller companies from being forced by bigger ones to report information that would otherwise be voluntary; eliminates requirements for due diligence on sustainability reporting for companies with less than 5,000 employees; and postpones the mandate for such due diligence until 2029. As this issue went to press this package still needed to be approved by member states.

REACH revision: As part of a regular review, the commission is developing a package of recommendations that would reaffirm commitment to protect against chemical hazards by speeding decisions about restrictions on hazardous materials and preventing repeats of past “mistakes” of inadequate protection. But it will also seek to make EU chemical companies more competitive by simplifying REACH rules and processes. It will aim where practical to ban hazardous per- and polyfluoroalkyl substances, PFAS, but back protections where not. The EC originally aimed to adopt its proposals by the end of 2025 but has postponed until 2026, which may push implementation into 2027.

Chemicals Industry Package: Aims to boost the competitiveness of the chemicals industry in the EU. It incorporates the REACH revision but includes other initiatives such as identifying chemicals where EU manufacturing capacity is at risk, especially those deemed critical, and seek to prevent capacity closures, especially by combatting unfair trade practices. It would support development of new sustainable chemicals, seeing this as a competitive opportunity for the bloc. This legislation is still being developed and is expected to be implemented by the end of 2026.

Bioeconomy Stategy: In November the EU updated this initiative to support innovation and investment in conversion of biomass into food, materials, products and energy. It aims to support budding European industry while also working toward sustainability.

Circular Economy Act: Would continue encouragement of recycling, aiming to double the level in Europe by 2030. Due for adoption in early 2026.

Motor Vehicle Block Exemption Regulation evaluation: The law, which aims to prevent anti-competitive practices in the automobile and aftermarket service sectors, is up for evaluation and potential amendment by 2026. The commission has already received input from various parties, including UEIL, which complained that the regulation has never done enough to ensure a level playing field in the providing of oil changes and supply of engine oil for replacement fill. The association called for free, unrestricted and early access to technical information about performance requirements for engine oils and other fluids; tighter curbs on practices such as using warranties to steer consumers toward certain engine oil brands; and ensuring that member states follow and enforce the regulation.

Tim Sullivan is Executive Editor of Lubes’n’Greases. Contact him at Tim@LubesnGreases.com