Behind the sleek efficiency of cars, trucks and machines lies a quiet environmental challenge: used oil. Every liter of lubricant poured into an engine or machine will one day reach the end of its service life. Once degraded, contaminated or burnt off, this oil becomes a potential pollutant if not responsibly managed. What happens next — whether it is discarded, burnt as low-grade fuel, or transformed through rerefining into valuable base oils — defines the sustainability story of the global lubricants industry.

Today, as the world intensifies its focus on circular economy models and carbon reduction, the way industries handle used oil is gaining unprecedented importance.

Why Recycling Matters

Improper disposal of used oil poses serious environmental risks. Just one liter can contaminate millions of liters of water, harm aquatic life and degrade soil fertility. Beyond protecting the environment, recycling and rerefining used oil delivers strong economic and resource benefits — reducing reliance on crude, conserving energy and turning waste into value.

These combined advantages have transformed how the industry views used oil, making re-refining a vital part of the circular economy. With advances in technology and growing regulatory support, this once-overlooked segment has emerged as a dynamic and sustainable business opportunity.

- Circular economy: Viewing used oil as a resource rather than waste closes the loop, reducing dependency on virgin crude oil.

- Environmental benefits: The more used oil is recycled, the less damage is caused to the environment.

- Energy efficiency: Rerefining consumes less energy compared to refining base oils from crude.

- Local economic growth: Collection and rerefining industries create jobs, reduce reliance on imported oil, and strengthen energy security.

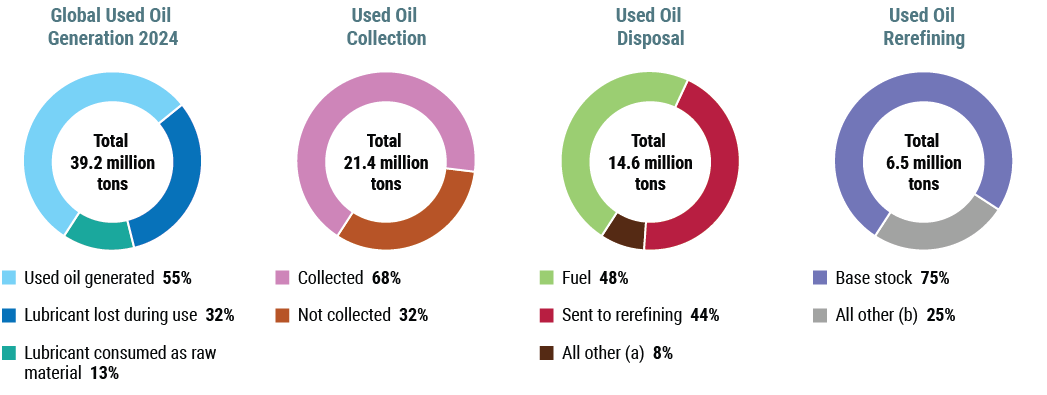

The journey of used oil involves three crucial stages: generation, which we refer to as upstream; collection, which is midstream; and disposal or downstream. At each stage, sustainability is either enabled or compromised. The success of any used oil rerefining industry is contingent upon each of these stages and how well they are integrated with each other.

- Generation of used oil is directly correlated with finished lubricant consumption. The higher the quality of lubricants used, the better the quality of the resulting used oil — which in turn enhances the efficiency and yield of rerefining processes, enabling the production of higher quality base oils.

- Collection remains the single biggest bottleneck in the used oil value chain. Effective collection and storage practices are essential to preserving used oil quality, which directly influences the production of high quality rerefined base oils. Markets with a more developed rerefining landscape typically feature a strong midstream segment — supported by robust infrastructure that ensures quality assurance, traceability and proper segregation of feedstock. In contrast, less evolved markets often struggle with fragmented collection systems, leading to contamination and adulteration, which ultimately result in lower quality rerefined base oils.

- Disposal pathways for used oil vary widely — from burning as heavy fuel to processing in refinery crackers or rerefining into base oils. These choices are often shaped by regulatory frameworks, or lack thereof, that either mandate specific disposal methods or offer incentives promoting environmentally preferred options such as recycling and rerefining.

Rerefining technologies such as filtration, thin-film evaporation, solvent extraction and hydrotreating determine the quality of the final output. Advances in solvent extraction and hydrotreating have enabled production of rerefined base oils that now rival, and sometimes exceed, the quality of virgin base oils. In mature markets, API Group II is the normal quality category for rerefined base oils, with some plants producing Group III grades, while less-developed markets still rely on basic processes yielding vacuum gasoil or low-end Group I base stocks.

Figure 1. Whittling Down the Used Lubricant Supply Stream

Source for all: Kline & Company, Inc.

Notes: Preliminary demand estimates for finished lubricant; a- Includes other application such as concrete demolding agents blended into high-sulfur fuel oil, ammonium nitrate fuel oil, etc.; b- Includes vacuum gas oil, marine diesel oil or regeneration of transformer oil

A Patchwork of Progress

Despite its potential, the rerefining industry remains a fraction of the global lubricants market. In 2024, an estimated 39.2 million metric tons of used oil were generated, but only 6.5 million tons ended up rerefined as base oils.

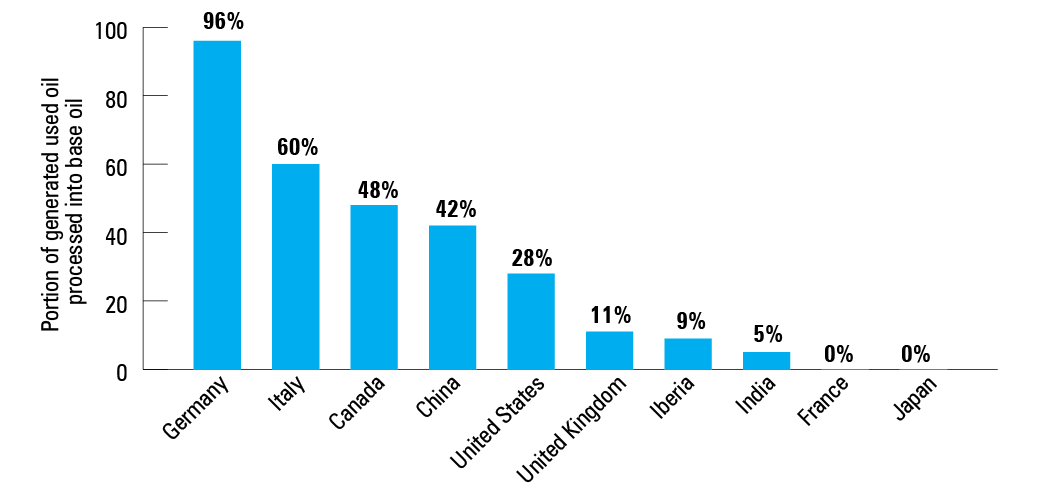

The progress of rerefining varies widely across the world and depends on a combination of regulatory, economic and market-driven factors. Kline’s proprietary RRBO Scorecard evaluates markets across multiple dimensions, including regulatory strength and enforcement, used oil quality, collection efficiency, rerefined base oil acceptance, market gap, and rerefining capacity and potential supply. This benchmarking framework provides a comprehensive view of each market’s current maturity and future growth potential.

The analysis covers key regions such as the United States, Canada, the United Kingdom, France, Germany, Italy, Iberia, China, Japan and India, revealing distinct contrasts as well as underlying similarities among them. Based on the findings, markets can be broadly grouped into three categories, reflecting different stages of rerefining evolution and opportunity. The groups are:

- Leaders: Germany and Italy showcase some of the highest rerefining rates. In fact, Germany even imports used oil to feed its rerefining capacity, while the United States leads in the production and supply of high quality rerefined base oils.

- Laggards: India, despite possessing a substantial pool of used oil and a broad refining base, continues to face challenges related to collection quality and technological sophistication. Japan, although generating high quality used oil, has an almost non-existent rerefining sector.

- Middle ground: China possesses substantial rerefining capacity. However, only a limited number of facilities utilize advanced technologies capable of producing high-quality rerefined base oils. France, meanwhile, benefits from a strong pool of high-quality feedstock but has relatively limited capacity dedicated to manufacturing premium-grade base oils.

While there is no universal blueprint for a successful rerefining ecosystem, certain common success factors emerge from leading markets. Efficient used oil collection and the consistent availability — or security — of high quality feedstock are defining hallmarks of markets positioned at the upper end of the rerefining spectrum. In contrast, markets that lag behind, such as India, continue to face challenges related to used oil quality and collection efficiency, although recent regulatory initiatives are beginning to address these gaps.

A Policy Turning Point

Across the world, extended producer responsibility policies are transforming used-oil management. The core principle is straightforward: Lubricant producers and marketers remain responsible for their products even after use. Unlike traditional policy tools that address a single stage of the chain, EPR integrates environmental accountability across the entire product life cycle. Governments, producers, marketers, consumers and independent collectors all share responsibility for ensuring proper collection and recycling. While governments set the framework, producers typically implement EPR schemes, and collectors play a vital role in channelling used oil to rerefiners — closing the loop of the lubricant economy.

Producers and marketers carry the greatest responsibility to develop efficient, sustainable systems for used-oil recovery. Although progress varies globally, EPR compliance is fast emerging as both a strategic and environmental imperative.

Formal EPR schemes come with administrative costs and typically redistribute funds from lubricant marketers, and ultimately consumers, to collectors and processors. Fees are usually applied to lubricants with regeneration potential, excluding those fully consumed during use or difficult to recover, such as greases. EPR models differ by design — some charge per-liter fees, others impose rerefined base oil content quotas, but their shared goal remains clear: to promote collection and regeneration while discouraging disposal and energy recovery.

Figure 2. Rerefining Rates in Selected Countries

One of the biggest challenges for rerefined lubricants has long been the perception of quality. However, rerefined base oils have made remarkable progress, moving steadily into the mainstream lubricant market. Advances in rerefining technologies have significantly improved product quality, narrowing both the performance and price gap with virgin base oils.

This transition is increasingly visible. With digitized collection systems, rigorous testing protocols and state-of-the-art refining processes, rerefined oils are now approaching parity with virgin oils. Leading lubricant companies are incorporating rerefined base oils into their blends, lending strong validation to the segment. Many are also becoming active participants in the used oil value chain, through partnerships, acquisitions or long-term offtake agreements with rerefiners. These collaborations are mutually reinforcing: Lubricant marketers enhance their sustainability credentials, while rerefined base oil producers gain market legitimacy and commercial scale.

Barriers and Challenges Ahead

Despite the promise, the rerefining sector faces persistent challenges:

- Collection bottlenecks. Unstructured systems in developing markets.

- Technology access. Capital-intensive advanced rerefining methods remain out of reach for smaller players.

- Scale. Most rerefineries are small and scattered. Scaling up increases logistics costs.

- Awareness and perception. End-users often remain sceptical of rerefined base oil quality.

Addressing these requires collaboration between governments setting policy, companies investing in technology, collectors ensuring quality segregation and consumers demanding sustainable lubricants.

The story of used oil and rerefined lubricants is one of transformation — from waste to worth, from pollutant to product. By embracing sustainability principles and circular economy thinking, the industry can turn a looming liability into a valuable asset.

The path forward requires overcoming challenges of collection, quality and perception. But the rewards — reduced emissions, conserved resources and stronger energy security — make the effort worthwhile.

In an era where sustainability defines competitiveness, rerefined lubricants may well emerge as the backbone of a greener, more circular lubricants industry.

This article drew from Kline’s recent “Sustainability, Used Oil and Rerefined Lubricants Report.”

Tim Sullivan is Executive Editor of Lubes’n’Greases. Contact him at Tim@LubesnGreases.com