Playing with my newborn granddaughter (eight months young now) is one of the most joyful themes in my life these days. While energizing me into life, she has also gifted me with three key insights during our play times: 1) Be in the present, 2) be entertained and entertain others, and 3) challenge the status quo.

How might these insights be applied to the lubricants industry?

The first two are predominantly sharing and caring, which I have enjoyed doing during my professional interactions. After all, progress in any industry relies, at least in some part, on the exchange of knowledge and ideas. This article, however, focuses on my granddaughter’s third key teaching regarding challenging the status quo. She is the inspiration for this article and therefore, I gratefully dedicate this to my granddaughter, Aeindri.

Challenge the Status Quo

Lubricant blending plants have become increasingly complex over the past few decades. When I first started my blending plant journey three decades ago, simplicity was in the foreground. There were fewer base oils, fewer additives, fewer finished formulations, fewer stock keeping units, and lesser competition and customer demands. Therefore, blending plants were simpler overall.

Today, it seems as if we are at the opposite end of the spectrum on just about every parameter. In addition to that, demand to serve the customer as well as cost to serve the customer are under severe pressure. Furthermore, the market scenario is evolving with the gradual infiltration of electric vehicles, and the product mix will undergo rapid changes in the next two decades.

That said, as lubricants blenders, we cannot continue doing what we have been doing and expect to be winners in an ever-changing market. To be frank, what has evolved over the past two or three decades in terms of blending technologies mostly involves automation and precision, which are important innovations but not necessarily ones that stem from a challenge-the-status-quo mentality. Instead, those innovations have met the most pressing needs of the time, necessitated by the primitive manual technologies prevalent before. In-line blenders, mass flow metering techniques and matrix manifolds have combined with state-of-the-art, high-speed filling lines and fully automatic warehousing systems to create the systems that we enjoy today.

However, it is quite possible that lubricants blenders’ contemporary needs are not being fully met. So how can these blenders challenge the status quo to better satisfy their needs now and into the future?

Compatibility Versus Complexity

Blending plants have been living with the traditional “compatibility matrix” issued by technical services. This forms the fundamentals of the production of lubricants end to end—right from the design of equipment to production and maintenance.

As can be seen in the mind map in Figure 1, there is extensive preparation required for changeover between production of different product families, which are differently classified in a compatibility matrix. The extent of preparation varies from simple draining of previously produced product to extensive cleaning and flushing with base oil or other fluids. Ultimately, this impacts the cost to serve. Overall equipment effectiveness (OEE) drastically reduces as well. In most cases, it has a 10%-15% impact from an otherwise practically achievable performance of 65%-70%.

Figure 1. Compatibility-Complexity Paradox

Waste generation, upkeep and management in terms of waste base oils and other products is painful, to say the least. Manpower effectiveness and productivity is also affected due to intermittent breaks because of such setup requirements in an otherwise fully automated process. Other softer aspects, which often go unnoticed, are the effects of personnel morale and quality deterioration due to these painful interruptions. All these are classical TIMWOOD (transport, inventory waste, motion waste, waiting and delays, overproduction waste, over-processing, and defects) problems from the Lean management perspective.

The challenge now is, “How do we deal with these classified incompatible products in the most cost-effective and quality-conscious way?” It is true that we cannot overlook the compatibility constraints in this case—although there could be some scope for improvement due to “overly conservative controls” implemented by the technical services (which I shall discuss in the next challenge).

My demand—or wish—is that we as an industry discover a way to blend product after product with no extensive preparation and setup requirements. The challenge has now been issued to the blending equipment manufacturers, namely the big, global equipment manufacturers but also smaller, regional players. Some pointers and a wish list for these equipment manufacturers are listed below:

- Blending equipment—mainly blending vessels and systems—should be manufactured with quick changing mechanisms whereby there is no need to flush the vessels during every changeover. Although I do not know of any immediate solution, perhaps some plug-and-play approaches may be possible.

- I wish for a system in which the internals to vessels are fitted with quick-changing parts, which can automatically change to the appropriate surface depending on which family It serves at any given time.

- I also wish for a system that would eliminate any need to flush product. It would also consolidate the many blending systems that have previously been dedicated to certain product families into one, which would increase capital investment.

I am visualizing a future blending world wherein the “compatibility matrix” will become more of a reference than a control, enabled by a highly efficient and effective self-adapting blending system for any production. This would be a win-win situation for investors and customers alike.

Formulation Versus Complexity

This subject of formulation controls has always been my favorite and is indeed paradoxical. Having been exposed to quality controls and the various systems of different companies during my work term, the topic is even more intriguing. What’s more, through decades of operations, the complications have multiplied. These complications may have been born from more stringent customer requirements, customer complaints, evolving product technology, etc. However, my belief is that such controls and requirements may have been built over and over on the prevalent conditions of the respective times, with possibly much lesser review of the previous controls. This has, I believe, resulted in the excessive fat in the process, so to speak.

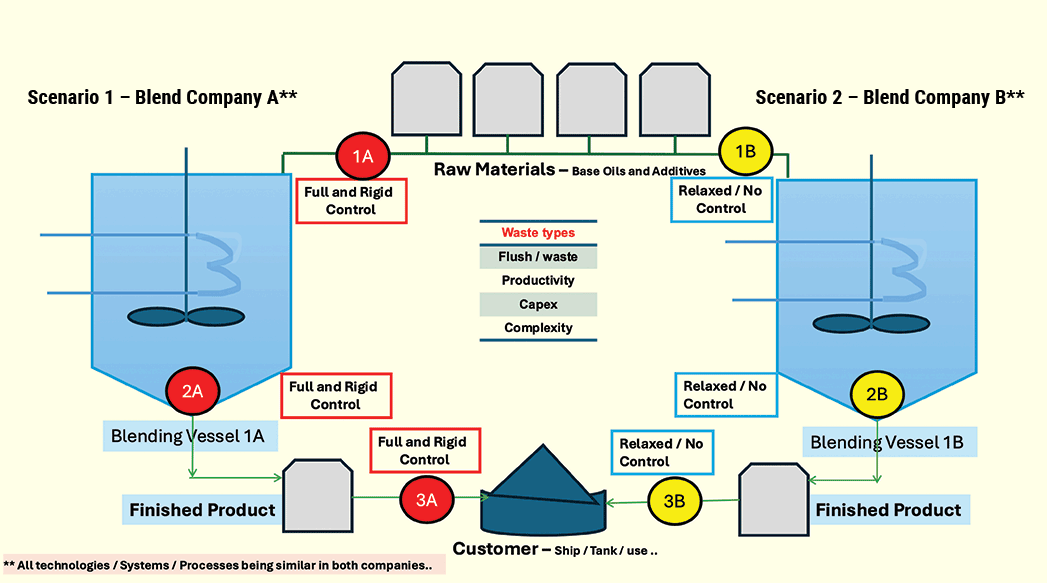

Based on the mind map in Figure 2, you can see a product that is serving a ship (or any other customer-facing end) that is being produced by two different blending companies. To begin, due to severe pricing and market competition, the customer is free to use any company’s product that is favorable to them. The customer receives the product into their system, meeting their internal quality control standards. With this, one can see different or no controls on certain aspects of manufacture from one company to the other.

Figure 2. Formulation Controls-Complexity Paradox

For example, I can remember the rigid and stringent filtration standard employed by one company at the last stage of supply to the customer as opposed to the most practical and perhaps more lenient standards employed by another company. Both are acceptable to customers; remember, the customer, in general, has the same source tank where products from two or more companies or brands are freely mixed without many specific restrictions.

This is just one example, but through the manufacturing and end-to-end supply chain, such varying practices are prevalent between brands. As in the previous challenge, impact to the cost to serve, OEE, productivity and some other softer aspects are all the results of such varying practices.

The challenge now is, “How do we deal with these differing formulation and quality standards in the most cost-effective and quality-conscious way?”

A possible challenge-the-status-quo wish list, as below, may aid in ultimately answering that key question:

- Formulation Development. How can lubricant manufacturers simplify the use of different base oils and other raw materials? Rigid specifications often lead to requests for additional facilities that require increased capital deployment.

- Formulation Standardization. While formulation is proprietary to each company, how can simplified formulations be standardized within certain constraints? There could be different approaches to different classes of products, and standardization could be attempted for generic and non-proprietary portions of a blender’s portfolio.

- Quality Controls and Management. There is a need to simplify and standardize, and some gross introspection may be required to do so. Overbuilt controls need to be dismantled. A more relaxed, smarter approach to controls is the need of the hour. Responding to past customer incidents or complaints may bring about additional controls. These, in many cases, should be temporary and on a case-to-case basis only.

These endeavors require lubricant formulators, as well as additive companies, to team up to create a more favorable outcome. It will be important to visualize a supply chain in which formulation-based controls are more selective and fewer in number for vital and specialized products, while all the rest enjoy a freer flow.

Conclusion

I have discussed two challenges in this article that have been prominent in my career. Admittedly, I have posed more questions than answers on the subject. But I recollect one of the more insightful conversations with one of my former colleagues. This person posited that “when you approach a topic, if you provide all the solutions and actions for a particular discussion, essentially the topic is closed, killing any other possible options.” That said, I would recommend starting with a more open-ended approach that could result in more options than one. I have experienced on several occasions some radical and divergent solutions as a result of such thinking.

So I must stress the value of such an open question- and challenge-based approach. While we may lack concrete solutions right now, this way of thinking is likely to yield answers in the times to come.

With this mindset, I look forward to the future of lubricant blending with both confidence and optimism.

Ganesan Ganapathi has 40 years of experience as a supply chain and manufacturing professional with leading oil companies such as BP, Shell, Total and Bharat Petroleum. While leading operations, supply chain and plant management with these companies, Ganesan has noteworthy contributions in the space of Strategic and Master Planning of Supply Chain and Manufacturing. He can be contacted via LinkedIn.