The Brazilian base oil market has been state-owned for some time. Petrobras and its network of subsidiaries have given the state dominance in the country’s oil sector and beyond. But the Jair Bolsanaro administration is already well underway with its plans to sell off half of the country’s oil assets, including two base oil refineries.

What is the administration’s reasoning for privatizing the country’s oil sector? The government claims privatization will spur the industry and help consumers by managing prices. However, some players in the region are unsure whether Brazil’s base oil market will undergo any significant changes as a result of the transition.

In 2019, the Brazilian government announced its intentions to sell 60% of its stakes in eight refineries run by Petrobras, retaining just seven of its own. Those eight refineries up for sale have a combined nameplate capacity of more than 1.13 million barrels per day, about half of Brazil’s national refinery footprint. These refineries are used to make a number of products, including diesel fuel, asphalt and special solvents.

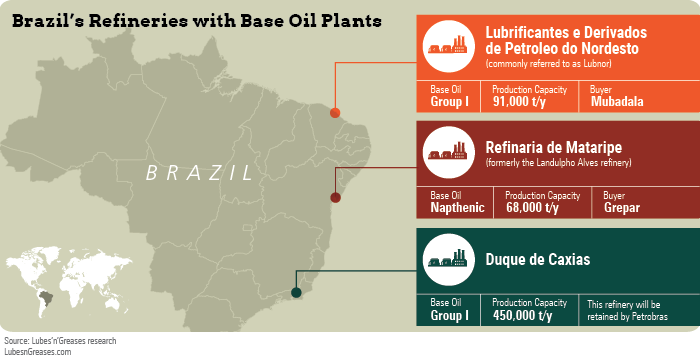

Brazil has three base oil refineries and one rerefinery. The largest base oil plant is the Duque de Caxias facility near Rio de Janeiro. It has capacity to make 450,000 metric tons per year of API Group I base stocks and is among the refining assets the government will retain.

The two other base oil facilities—one in Itaborai and another in Fortaleza—were previously owned by Petrobras and have been sold, pending antitrust approval.

The former was purchased by Mubadala, an investment management firm based in Abu Dhabi, United Arab Emirates, for U.S. $1.65 billion. The Refinaria de Mataripe (formerly the Landulpho Alves refinery) has capacity to make 91,000 t/y of Group I base oil, though its actual production dwindled to just 2,000 t/y in 2020.

The latter facility was purchased by a consortium named Grepar in June for $34 million. Formally known as Lubrificantes e Derivados de Petroleo do Nordeste and dubbed the Lubnor refinery, it has capacity to make 68,000 t/y of naphthenic base oils—the only domestic source of such base stocks. That consortium includes asphalt supplier Greca Asfaltos, which has had no prior base oil operations.

Privately-owned Lwart runs its own 78,000 t/y Group II rerefinery and is the only source of Group II base oils in the country.

The Bolsanaro administration says privatization will benefit the industry by increasing competition and driving down prices for consumers. The plan to sell came under fire from Brazil’s Federal Senate, saying the initiative was taken without analysis by the National Congress. The Brazil Federal Supreme Court later allowed the sales to proceed.

“I also consider to be quite relevant that there are much better economics and financial prospects for Petrobras investing in [exploration and production] than investing in oil refining,” said Claudio Silva, executive director of consulting firm LubeKem.

LubeKem estimated that in the past five years Petrobras’ exploration and production gross margin, already discounting royalties and other government participation, has been triple that of its oil refining operations—and even higher in 2022. The divestment of oil refining, old oil fields and other downstream business helps Petrobras not only reduce long-term net debt but also allows for further investment in its current refineries and more oil-rich fields.

A key aspect of Petrobras’ interest in oil exploration and production is the pre-salt layer off Brazil’s coast. The area is a major oil and gas reserve, stretching approximately 500 miles up the coast and 125 miles inland. Petrobras said it was producing 1.5 million b/d of oil from the region as of 2018, an exponential increase from just 41,000 b/d in 2010.

“Although some market analysts believe otherwise, the world will need to continue investing in fossil fuels probably until the middle or even the end of the 2030s, and in this scenario, the Brazilian pre-salt layer will represent a major sustainable competitive advantage both in low lifting costs and in lower carbon footprint compared to most global oil fields,” Silva said.

According to the United States Energy Information Administration, Brazil is now within the top 10 of global oil producers, just behind the United Arab Emirates.

“Another important issue favoring the focus on investments in [exploration and production] is the huge increase of Brazilian oil exports: 120% in the past 10 years to over 1,320 b/d in 2021,” Silva said.

“In my opinion, after completing its divestment plan for all refineries, these new players and refinery configurations are not expected to benefit customers with lower fuels prices, which has been one of the main arguments used by the government to justify these divestment plans, since Brazil will continue to be dependent on fuel imports,” Silva added. “In spite of that, I am favorable to the sales of these refineries, as the entry of new players in the Brazilian market will also mean new investments in our downstream markets and, after this divestment, Petrobras will be able to concentrate efforts focusing more closely on its strategic assets both upstream and downstream.”

Factory assets changing hands can lead to uncertainty about whether new owners feel the base oil facilities are worth keeping. Luiz Guglielmi, executive director of Lubnor refinery owner Grepar, said that base oil production is part of the company’s future plans.

“The production of base oils and the market for this product was part of the decision-making process for the investment and acquisition of the refinery in Ceará. Our business strategy is to keep expanding, not only in our area of operation, but also in markets that we believe have great potential, such as base oil,” he told Lubes’n’Greases.

“Our business plan aims not only to maintain but also to expand the production of base oils, investing in the future, in doubling production, improving the quality of our industrial oils, and reducing logistics costs for the entire supply chain,” he said.

|

“Our business strategy is to keep expanding, not only in our area of operation, but also in markets that we believe have great potential, such as base oil.”

– Luiz Guglielmi, Grepar |

Acelen, the Brazilian subsidiary of Mubadala which has been tasked with operating the “RefMat” refinery, has yet to indicate what its plans are for the base oil facility.

Silva thinks it could follow Grepar’s commitment. “I think that to keep both Group I base stock production at [RefMat] and naphthenics production at Lubnor would make sense to add value on the overall refining portfolio of each company,” he explained. “Maybe even some small investments to debottleneck or to marginally increase base stocks production in each refinery could make sense, too.”

At the end of last year, Petrobras said it planned on building a 600-kiloton per year Group II base oil plant—among other upgrades—at its GasLub site in Itaboraí. As for now, however, Petrobras said the project is still under study.

Silva also speculates there could be an opportunity for the sold-off refineries that do not house a base oil facility to invest in one. “It could be a window of opportunity in some of these refineries since the Brazilian lubricants market is one of the largest worldwide,” he said. “Its lubricants demand is expected to increase above global averages in the next years and base stock imports are already over 50% of overall demand.”

Brazil was the sixth-largest lubricants market in the world in 2019, according to consultancy Kline & Co.

Domestic base oil production has been on the decline every year for almost a decade. Brazil imports about half of its base oil supply from refiners along the United States Gulf Coast, most of which is Group II. Base stocks like Group III and polyalphaolefins are also imported.

“Since production peaked in 2013 and 2014 with over 1,650 b/d, including rerefining, overall Brazilian base stock production has been dropping year after year,” Silva said. “In 2020 due to COVID, local production was only about 1,200 b/d but recovered in 2021 to 1,530 b/d.”

Even with the refinery sales going through, Silva does not envision the situation changing “significantly” in the near-, mid- and maybe even long-term. The potential construction of a new Group II plant does not necessarily guarantee increased domestic production and less imports.

According to Silva, there is no vacuum gas oil production at Petrobras’ Duque de Caxias site where its Group I base oil plant is located, so it will need to connect that refinery and GasLub to supply feedstock to a Group II plant.

“For now, it is not clear if Petrobras will continue producing Group I at [Duque de Caxias] after starting operations at GasLub, and maybe there’s not enough VGO to run both base stock plants in the future,” Silva said. He added that Petrobras is expected to release a five-year strategic plan at the end of 2022, which may provide clarity.

Guglielmi is more optimistic about the landscape shifting. “Brazil currently has a favorable scenario for growth in the domestic market in terms of consumption of base oils. We have a continental territory, with a very high demand, and because we do not have a plant that fully meets our needs, we had to bet on imports of a product that is also produced in the country,” he said. “That is why we believe that growth in imports only occurs today due to a repressed demand that is not met internally. But that will change in the coming years.”

Will Beverina is assistant editor for Lubes’n’Greases. Contact him at Will@LubesnGreases.com