Your Business

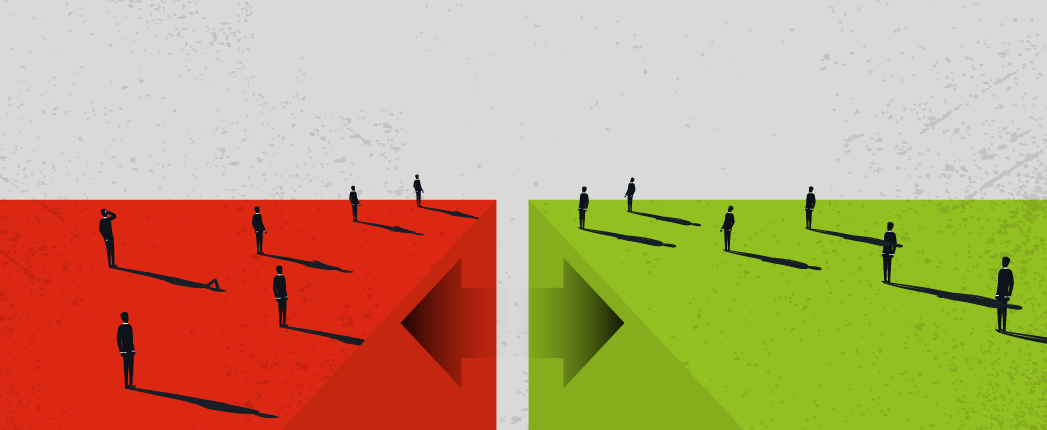

Large corporate conglomerates are sometimes in, sometimes out.

The recent news that General Electric, founded 129 years ago, is splitting into three independent companies seems to be indicative of a trend. Toshiba—which dates back to 1875—has announced that it will also split into three companies. Johnson & Johnson will split into two. Royal Dutch Shell—which became one company in 2005—will change its name to Shell and relocate its main offices to London.

Interestingly, Shell mentioned that its more efficient organization will enable it to “demerge” (read: spin-off business activities) if it wants to.

The reasoning behind the corporate urge to slim down is that it would unlock shareholder value, focus management attention on core businesses and eliminate less profitable or socially unacceptable activities.

Previous arguments for becoming a conglomerate were that a company’s management team was thought to be skilled enough to manage unrelated industries and that diversifying would reduce risk by counterbalancing its primary businesses.

Petroleum companies have favored the conglomerate format in the past; the 1960s and 1970s were particularly active years.

Mobil bought Montgomery Ward and Container Corporation of America in 1974 and sold what remained of its failing operations in 1988.

The Atlantic Richfield Co. (ARCO)merged with Anaconda Copper Mining Company in 1977 and purchased Solar Technology International—renamed ARCO Solar—that same year.

The Anaconda copper mines were closed in the early 1980s, leaving severe environmental problems, and unprofitable ARCO Solar was sold in 1989. When BP America acquired ARCO in 2000, it inherited Anaconda’s Montana mining mess, the largest Superfund site in the U.S.

Afterward, ARCO chief Robert Anderson said he “hoped Anaconda’s resources and expertise would help launch a major shale-oil venture but that the world oil glut and declining price of petroleum made shale oil moot.”

Coal was attractive to oil companies. In 1966, Conoco purchased Consolidation Coal, which was sold by duPont after it bought Conoco. Sohio bought Old Ben Coal Company in 1968 and Kennecott Copper in the 1980s.

Shell purchased Massey Coal in 1980, bowing out in 1987. Mobil bought Morris Coal. Occidental Petroleum purchased Island Creek Coal. Ashland Oil acquired Arch Mineral with Hunt family help. And Exxon—which was promoting itself as an “energy company”—bought Monterey Coal.

But it seems Exxon was not solely an energy company. It announced in the mid-1970s that it would form an office-systems division to compete with such companies as Xerox and IBM. That entity, based in Stamford, Connecticut, acquired and integrated several small high-tech companies to help it design and manufacture Vydec word processors, Qwip faxes and Qyx typewriters. (Does anyone remember these?)

Exxon expected to make $1 billion from the sale of office equipment but ended up writing off that amount when it closed the division in 1984.

Esso Rent-A-Car—a business that Exxon initiated as a pilot project in the mid-1960s in the Boston area—probably could have made it, though.

A group of dedicated, innovative employees set up facilities and rented the wildly popular Ford Mustang to the public with astonishing success. The venture was profitable, but Exxon pulled the plug a few years later because it was too small and not related to the company’s core business.

Makes you wonder why they tried it in the first place.

Jack Goodhue, management coach, can be reached at goodhue@aol.com