The lubricant supply chain is both long and complex, and no group is more aware of that than lubricant distributors. Because distributors deal with a wide variety of products with different chemistries, the nature of the job requires them not only to understand the supply chain and how they operate within it but also to ensure product quality maintenance and reliability.

Why is it important to reliably maintain a lubricant in its original state during its long journey from the manufacturer to the customer?

“If the customer has accurately defined application, need and quality expectations, then it is the lubricant in this original state that was paid for; vetted in laboratory, bench and equipment testing; certified, qualified and licensed to meet various industry, original equipment manufacturer and quality standards; and found to work without issue in the application,” Michael Roe of MJR Lubricant Distribution Consulting and Auditing said at the Society of Tribologists and Lubrication Engineers Virtual Annual Meeting and Exhibition in May.

To ensure that lubricant integrity is not compromised at any point along the supply chain, companies should have robust quality programs in place. “This is particularly true for lubricant distributors,” Roe said, “as they are faced with a complex and daunting supply chain with multiple components.”

According to Roe, the supply chain begins and ends with the customer application. “It starts there because the customer needs a lubricant for a specific purpose,” he said. “It truly ends when the lubricant has performed satisfactorily in the application for the life of the lubricant.”

However, the line from point A to point B is not often a straight one, and several supplier-customer relationships—like those between manufacturers and distributors or distributors and consumers—help to bridge the gap. “There are a number of different kinds of lubricant products involved” in the supply chain, Roe said. “Many manufacturers and many customers. Primary entities involved in the supply chain are the customer, the manufacturer and various intermediaries—chiefly distributors and transporters.”

What’s the Problem?

Along with a large number of components in the supply chain comes a higher risk of quality issues. A significant problem facing distributors is the commingling or contamination of products. “There must be proper handling and segregation of lubricant products from each other, from non-lubricant products and from contamination,” Roe said. “This ultimately requires dedicated or controlled product handling equipment and proper change of assignment procedures for the products involved.”

Product contamination can occur any time the product is handled, Roe said. It is exacerbated by management oversight; inadequate or incorrect equipment, processes and procedures; and inattention. “Internal sources of contamination include inadequate purging, filtration and crossover,” Roe said. “External sources include incorrect or missing identification, contaminant ingress through improper storage or handling, lack of training or procedures, tampering, and failure to segregate non-conforming product,” he said.

Commingling or contamination of products can lead to changes in physical and chemical properties. “A lubricant’s physical and chemical properties must be maintained throughout the supply chain to properly lubricate in the application,” Roe said.

|

“There must be proper handling and segregation of lubricant products from each other, from non-lubricant products and from contamination.”

— Michael Roe

MJR Lubricant Distribution Consulting and Auditing |

For fluid lubricants—like engine oils and hydraulic fluids—the primary physical property that must be maintained is viscosity, while NLGI consistency grade is vital for greases, Roe said. “Distributors should be able to accurately check the viscosity of their products for at least one of the specification temperatures.”

Maintaining product chemistry is essential. “For most fluid lubricants, the primary chemical property that must be maintained is the additive content,” Roe said. “Additive content is identified by a variety of methods,” including spectrometric analysis.

For grease, the integrity of the thickener system must be preserved. “The grease thickener can be affected in such a way—for example, by shear—that the grease lessens in consistency,” Roe said. “In rarer cases, the grease may also increase in consistency due to prolonged storage, for example.”

A motor oil sample is tested for viscosity. Viscosity is a vital lubricant property that must be maintained throughout the supply chain.

© Alexey Rezvykh / Shutterstock.com

Fluid lubricants formulated with different base stocks “should be handled either with dedicated systems or with proper change of assignment on common systems,” Roe said.

Greases of a specific thickener type and color should be handled with dedicated systems, too. “Common systems are difficult to purge,” Roe said. Greases that are made with the same thickener but that differ in color must also be kept separate to avoid appearance issues.

If different grease thickener types must be handled together, distributors should perform a compatibility test—such as ASTM D217—beforehand, Roe said.

Because commingling and contamination can compromise the integrity of lubricants, lubricant transfer is an activity of concern for many distributors. “Transfer activities need to occur under a rigid change of assignment method,” Roe said. Changing assignment refers to switching from one product to another during a transfer. Change of assignment methods include dedicating systems, drain drying, flushing, reverse pumping, pigging, air blowing and pushing.

“The best approach is to have dedicated handling systems,” Roe said. “Where the ability to dedicate is limited, common systems may be used with products of the same additive chemistry.”

Properly naming and identifying products can mitigate issues during lubricant transfer. “Product names can be very complex and similar at the same time,” Roe said. But to ensure proper handling, it is important to know what product is being handled and what its chemical and physical properties are.

Lubricants—especially those with different chemical makeups—must not only be segregated from each other but also from any non-lubricant products. “The typical lubricant distributor will handle a variety of non-lubricant products,” Roe said. “These include ancillary automotive and diesel products: engine coolant, antifreeze, windshield washer fluid, diesel exhaust fluid and brake fluid. They also include fuels—typically gasoline and diesel fuel. All non-lubricant products must be vigorously segregated from lubricants.”

In the same vein, equipment must be adequately purged of any cleaning fluids before a change of assignment is completed. “There are a variety of cleaning fluids available during change of assignment, chief among these being diesel fuel,” Roe said. “Diesel fuel is often used to clean equipment from previous lubricants because of its ability to readily solubilize most oil- and polyalphaolefin-based lubricants. As such, it is critical to ensure that all the diesel fuel has been removed from the equipment after cleaning.”

Preventive and Detective Controls

“While R&D does a terrific job at formulating products to provide outstanding performance in customer applications,” Roe said, “its efforts would be of little value if effective preventive and detective controls are not in place throughout the supply chain.”

Preventive controls keep errors or irregularities from occurring in the first place, while detective controls find errors or irregularities that have already happened, assure their prompt correction and prevent their occurrence in the future. “The sooner an error is detected,” Roe said, “the sooner it can be prevented from spreading further into the supply chain.”

An example of a preventive control is a matrix chart in which products are arranged in all the possible ways they can be handled in a common system. Each system is identified based on product category, such as industrial gear oil or hydraulic fluid. The prior product is shown across the top of the matrix, while the product to be handled next is displayed along the left side. “Based on product technical experts and compatibility, the change of assignment method is found where the two products intersect on the matrix,” Roe said.

However, using a matrix for change of assignment is recommended only for fluid lubricants, Roe said. Greases should be handled only with dedicated systems based on thickener type and color.

Documented procedures and records are also essential for maintenance and reliability in the supply chain. “There should be a documented procedure for every critical activity,” Roe said. “Documents and records provide evidence that effective preventive controls are in place and in practice.” They also clarify rules and responsibilities, while reducing the probability of errors resulting in quality incidents.

Procedures should be written, current, comprehensive and readily available to all those who need them to perform their job. Procedure revisions are triggered by new equipment, products, packaging, employee safety issues, customer feedback and quality incidents.

“A lack of, an incomplete, or an unfollowed documented procedure is a leading cause of product quality incidents,” Roe said.

Training is also an integral preventive control. “Everyone engages in some kind of training,” Roe said. Training must be competent, verified and sustained. “Training cannot be a one-time exercise. It is of little value if it’s not being constantly reinforced, maintained and sustained by individuals, supervisors and management.”

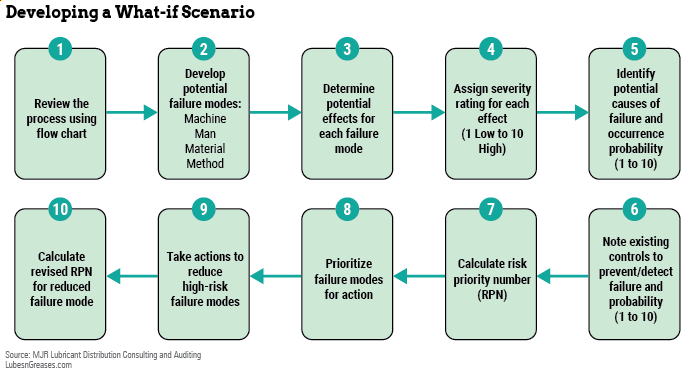

What-if scenarios are another preventive control. Also known as failure mode effects analysis or risk assessment, what-if scenarios help to identify critical activities and consequences of failure. “A typical what-if scenario is a method of identifying and preventing or mitigating process problems before they occur. The basic idea is to determine all the possible ways something can fail, how bad it can be, all the potential causes and the likelihood of occurrence.”

Detective controls—such as quality programs, investigations and audits—are also useful in maintaining the integrity of the supply chain. “The quality incident investigation process is important to immediately address an issue, determine a root cause and take corrective, preventative and sustainable actions,” Roe said. “Quality incidents, especially if repeated or not handled immediately, can lead to strained customer relationships.”

Similarly, quality audits are essential to ensure that equipment, training and procedures are in place to satisfactorily handle lubricant products. Audits often lead to efficiency improvements, while detecting and preventing potential quality incidents. Roe suggested that audits should be conducted by someone as independent as possible from the process being audited. However, the auditor should have a basic knowledge of the process.

The steps of a quality audit process include initiating and preparing the audit, reviewing related documents, conducting the audit, reporting audit results, and following up on those results.

Another detective control is sampling, testing and retaining, also known as ST&R. This should be in place for all critical activities, Roe said. “Employees need to be trained on ST&R, particularly in how to take samples and evaluate test results—whether a test is a pass or fail,” he said. Samples that are taken must be representative and non-invasive so as not to introduce contaminants.

Sydney Moore is managing editor of Lubes’n’Greases magazine. Contact her at Sydney@LubesnGreases.com