The pandemic affected different companies in the lubricants industry differently. Which ones emerged triumphant, and which ones took a few hits?

(Editor’s note: For purposes of comparison, all financial results covered in this article are given in U.S. dollars. Currency conversions, where needed, were calculated in mid-April at then-current rates. All results are for the 2020 calendar year, even for companies operating on different fiscal years. For companies with significant operations in other sectors, results shown are for units focused on lubricants or base stocks.)

The COVID-19 pandemic caused generational upheaval to economies and industries around the world, the lubricants industry included, destroying demand, disrupting supply chains and creating stiff new challenges to operations and employee safety. When the crisis began, analysts forecast that 2020 would be a dark year for many companies.

For many, that turned out to be true—but not all. Some lubricants, base oils or additives businesses not only got by but managed to increase profitability last year, even as competitors struggled. Analyzing such performance is generally not easy in the lubes industry, where relatively few players publish financial results. Still, exceptions can be found in a variety of sizes, locations and business models. Lubes’n’Greases examined performance of 33 companies in the industry in order to draw conclusions about how companies were able to survive and even thrive during a pandemic.

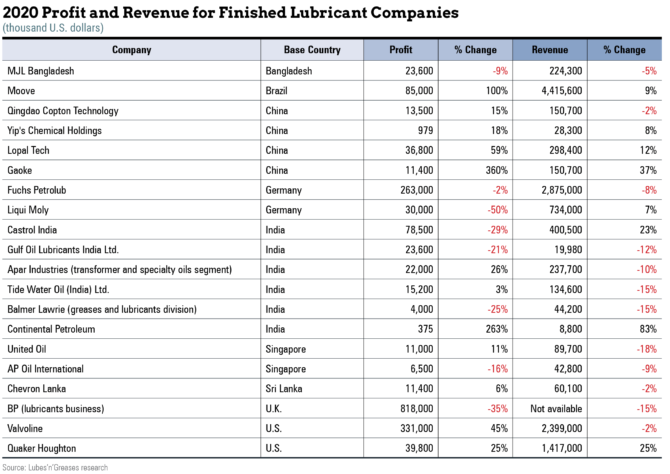

COVID-19 affects different people differently. Similarly, it has also had varying impacts on companies in the lubricants industry, even those that seem similar. Take for example BP’s lubricants business and Valvoline, both among the world’s largest finished lubricant suppliers. Both sell their products around the globe, though London-based BP is significantly larger and operates in more countries than Valvoline, which is headquartered in Lexington, Kentucky, United States.

Both companies performed at opposite ends of the spectrum last year. Underlying replacement cost—the closest thing to profit that BP reports for its lubes business, fell a sobering 35% to $818 million. Valvoline’s profit, meanwhile, jumped 45% to $331 million.

As is often the case, results were partly due to factors that go beyond the making and selling of products. Approximately half of Valvoline’s profit stemmed from one-time credits related to pensions and accounting for employee separation.

Filtering out those impacts, the combined operating income of Valvoline’s three business segments still jumped 7% to $464 million during the 2020 calendar year. Examining those results sheds light on some of the reasons it fared so much better than BP’s lube unit. Valvoline’s profits came solely from its lubricants segment, which covers only North America but does not include performance of its chain of oil change service centers, which numbers nearly 1,500 company-owned and franchised locations. The segment’s operating income jumped 22% to $203 million, even though sales revenue dipped 8% to $932 million.

The company attributed that performance to three main factors: a cost-cutting initiative begun in 2019, lower raw material costs, and an increase of several percentage points in the portion of sales constituted by premium products.

Valvoline’s quick lubes segment managed a 1% increase in sales revenue, but its operating income dipped 2% to $174 million. Its international segment held operating income at $87 million while watching sales revenue fall 5%.

BP provides much less information about its lubricants business, explaining in a Feb. 2 earnings statement that the result “reflects significant demand impacts” stemming from the various measures governments took to curb the pandemic. BP did not disclose its lubricant sales volumes for 2020 but did say they fell 15%. The fact that an approximation of income fell more than revenues means that the gross margin of BP’s lubricant business decreased, in contrast to Valvoline’s.

One of the few other very large lubricant marketers covered in this analysis—Fuchs Petrolub SE—performed in between Valvoline and BP last year. The company—which is based in Mannheim, Germany—reported that its profit fell 3% to $263 million, while revenues declined 8% to $2.4 million.

However, it is important to note that these three large suppliers focus on different parts of the lubes industry. Valvoline’s business is heavily weighted toward automotive products, especially engine oils, while Fuchs mostly focuses on products for industrial applications. BP’s lubricants business is a big player in both segments.

Similar dichotomy could be seen in two of the world’s largest metalworking fluids companies, Quaker Houghton and Yushiro Chemical Industry Co. Both companies are among the world’s half dozen largest suppliers of metalworking fluids, but their fortunes diverged significantly during the year of the pandemic. Quaker Houghton, which is based in Conshohocken, Pennsylvania, U.S., reported that its profit fell 5%—relatively mild considering the impacts of the pandemic—while its sales revenue jumped a whopping 25%. Yushiro, which is based in Tokyo, starts its fiscal year on April 1 and does not report results for its fourth quarter, so calculating its performance for the full 2020 calendar year is not possible. For the three quarters that are available—running from April through December—the company had an operating profit of $3.9 million, which was 89% less than the same period of 2019. Revenue fell 17% to $410 million.

Both companies make substantial portions of their sales to the automobile industry, so their businesses could have expected to struggle. Around much of the world auto sales plummeted during the middle half of the year, and many OEMs temporarily closed factories. Yushiro cited the industry’s contraction in posting a loss for the quarter ended Sept. 30.

But while Quaker Houghton rebounded as the auto industry began to recover during the final quarter—all of its profit for the full year came during the last period—Yushiro remained in the red.

Part of Quaker Houghton’s success can be credited to lucky timing. In 2019, Quaker Chemical completed a sizeable merger with Houghton International to create the world’s largest supplier of industrial fluids. The new company cited higher-than-expected synergies from the combination as one reason for its performance. The merger also sharply increased the company’s cash flow, allowing it to reduce debt and to complete acquisitions of three other companies between December and April.

“While COVID-19 presented many challenges for the global marketplace—including double-digit declines in our end markets—we were able to mitigate some of the impact on the company through our market share gains and acquisitions,” CEO, Board Chairman and President Michael Barry said in a February press release.

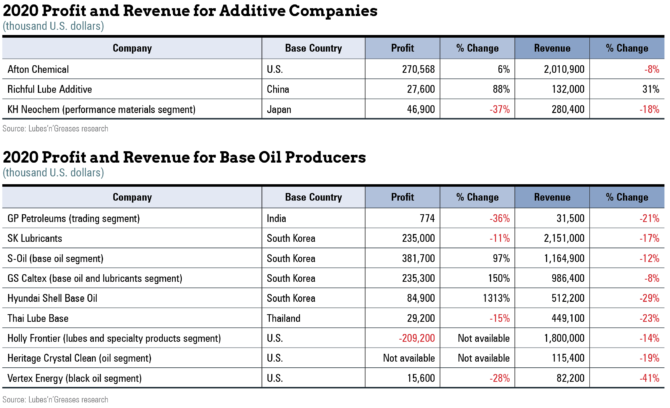

As a sector, base oil producers had some advantages over other parts of the industry in 2020. According to Amy Claxton, CEO of My Energy Consulting, base oil companies generally performed well because “base oils are used across broad, unrelated industries (tires, cosmetics, construction, transportation, industrial plants, etc.). This is the ‘golden ticket’ because losses in some downstream uses are offset by gains in others.”

Good margins proved to be a game-changer for base oil producers. When crude oil prices crashed at the start of the pandemic, profit margins for base oils fattened significantly. This created a bright spot for a petroleum industry that overall was rocked by the pandemic, and suppliers scrambled to sell as much base oil as they could.

Unfortunately, base oil producers also faced constraints. Claxton explained, “Supply versus demand is always the bottom line. On a global basis, we are long on Group II and Group III, so logical conclusions can be drawn regarding which base oil producers had better margins.”

Three South Korean refiners—S-Oil, GS Caltex and Hyundai Shell Base Oil—all posted big gains in profits, ranging from 97% for S-Oil to more than 1,300% for Hyundai Shell, despite drops in sales revenue.

The most profitable of the South Korean base oil suppliers, SK Lubricants, headed in the opposite direction, as its profit dropped 11% to $2.2 million. SK Lubricants’ sales revenue also fell 17%, which is a bit more than S-Oil’s but less than Hyundai Shell’s.

Last year yielded varying results for other base oil suppliers with earnings to monitor. In India, GP Petroleums’ trading unit—which deals in base oils—managed a 36% increase in profits, largely offsetting a 29% drop in profitability of its finished lubes production and marketing unit. For Mumbai-based GP, it still added up to a 25% drop in the units’ combined profitability.

Bangkok-based Thai Oil reported a 15% drop in profitability for its base oil business—Thai Lube Base PLC makes Group I stocks—on a 23% decline in revenue. Curiously, the company cited narrower spreads along with lower volumes.

In the United States, Holly Frontier posted a $209.2 million loss in operations for its lubricants and specialty products unit, compared to a $129.1 million loss in 2019. Revenue for the unit, which fell 14%, comes largely from sales of base oils and finished lubricants.

Claxton explained that U.S.-based rerefiners suffered during the pandemic, too, mostly because they “produce base oils suitable for automotive uses, which are highly exposed to consumer behavior and demand for passenger car engine oils.”

A prime example, Heritage-Crystal Clean reported that its revenue fell 19%. President and CEO Brian Recatto noted that the company had to idle its Indianapolis rerefinery for most of the month of May due to the pandemic.

Vertex Energy reported decreases in profit and revenue of 28% and 41%, respectively. Base oil sales revenue fell 21% to $27.2 million but was buoyed by a 37% jump in revenue from oil collection services, to $7.8 million.

In some cases, geography also seemed to play a role in the fortunes of lubricant companies last year, as the pandemic’s impacts varied between nations.

All four of the Chinese companies examined for this article enjoyed increases in profits as well as revenue, while four of six Indian companies reported decreased profits and all posted lower revenue. China was one of the first nations where numbers of COVID-19 cases fell off and therefore one of the first to lift major lockdown policies. Beijing reported that the nation’s gross domestic product swelled by 2.2%, making it one of the few growing economies in 2020. In contrast, India was still struggling to control its outbreaks as this issue went to press. Some estimates peg the shrinkage of its GDP in 2020 at about 10%.

Tim Sullivan is executive editor of Lubes’n’Greases. Contact him at Tim@LubesnGreases.com.

Sydney Moore is managing editor of Lubes’n’Greases magazine. Contact her at Sydney@LubesnGreases.com.