There are approximately 120 large fuels refineries worldwide that produce base oils as part of their overall product slates and about another 20 integrated refineries that have a significantly greater focus on base oils as a total percentage of their product output, according to Amy Claxton, CEO of My Energy Consulting.

Because the majority of base oil plants are integrated into fuels refineries, it stands to reason that operations at these refineries could directly affect what goes on at their base oil plants and vice versa. What is less obvious is exactly how they influence each other.

Tyler Kruzich, external affairs advisor for downstream and chemicals with Chevron, explained that competition for feedstocks is often a major factor. “Base oil plants consume similar feedstocks—vacuum gas oil —as hydrocrackers and fluid catalytic cracking units. The base oil plants compete with those downstream units for feed, typically derived from running crude oil. Other petroleum products, such as mogas [gasoline], jet fuel and diesel, will compete with base oil for the incremental intermediate feedstock.”

Claxton agreed: “With crude as the starting feedstock, and vacuum gas oil as the primary feed in North America to solvent processing and hydroprocessing facilities, VGO is a shared commodity between fuels and base oil units.” Each refinery employs coordination and economics groups that formulate short- and long-term plans for each refinery processing unit to ensure that each unit receives adequate volumes of the feedstocks necessary to produce on-spec fuels and base oils, she continued.

In addition to feedstocks, Claxton told Lubes’n’Greases that base oil units are integrated into refineries in many other ways. The refinery’s fuel and other utility systems, hydrogen systems, laboratories, refinery-wide maintenance groups, docks and loading ramps are commonly shared by both fuels and base oil processing units.

Pandemic Forces a Rebalance

While balancing the manufacturing of various products at refineries is a delicate dance during normal times, it seems to have become even more difficult since the onset of the COVID-19 pandemic. Top of mind for many refiners right now is how the pandemic has affected and will continue to affect refinery operations, as well as the decisions and changes that must be made to deal with the fallout from the virus.

Most obviously, there has been a precipitous drop in demand for crude oil and refined products in the wake of lockdowns across the globe. Demand for refined and finished products, including jet fuel and passenger car motor oils, fell off and forced refiners to significantly cut production rates as the downstream market shrank. With less crude being processed, the availability of feedstocks used to make refined products such as base oil has been limited.

“The length of the [pandemic] determines if, rather than when, we return to normal,” Amanda Hay, acting managing editor for the Americas with ICIS, said during the events and consulting company’s Pan-American Base Oils & Lubricants Virtual Conference in December. “How long will refiners temper rates because of weak demand?”

She explained that current refinery utilization rates are sitting at about 75%, which is 10%-15% below normal rates in the Americas. She also reported that ICIS does not anticipate a return to pre-pandemic levels until 2022 or 2023. “By most accounts, we expect the global markets to take well into 2021 before any signs of a true demand recovery begin.”

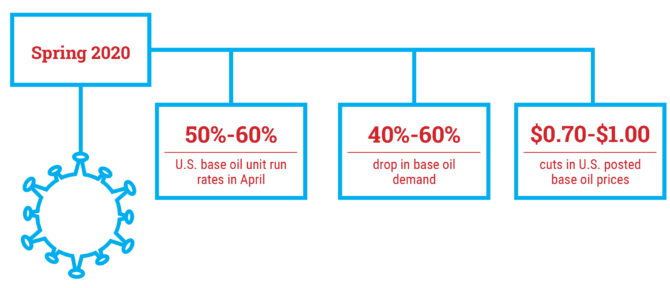

Before a slight rebound in demand at mid-year—with the utilization rate in the United States inching back up to 82% before a rash of hurricanes hit the Gulf Coast—total refinery utilization in the country hit a multi-decade low in April. During that month, run rates fell to 67.6%, and base oil units were likely even lower at around 50%-60%, by Hay’s estimate. “Refinery rates have not been this low for this long for at least as far back as 1990,” which is the year that the U.S. Energy Information Administration began keeping such records, she said.

Chevron’s Kruzich confirmed that “the pandemic has caused demand destruction to mogas, jet and diesel fuels. This has reduced the incentive to run crude oil to the refinery and associated downstream units. Lower crude rates have decreased the production of intermediate VGO derived from crude, and the tradeoff between fuels production and base oils continues. Current base oil price strength has tended to incentivize base oil production relative to fuels.” This is the reverse of what had been industry practice for a couple of years leading up to the pandemic, when refineries diverted feedstock to fuels production because of narrower base oil margins.

Hay expressed similar views, saying that “refiners are not increasing their crude runs because fuels demand has not yet returned to normal levels.”

The oversupply of base oil has also contributed to the challenges refiners face. “We entered the lockdown period quite oversupplied,” said Hay, “and this was made worse when demand retreated.”

In 2020’s second quarter, many refiners’ storage tanks were full thanks to the sudden drop in demand. Some of the oversupply was tossed back into the VGO pool to make more in-demand products, but the problem has forced refiners to keep their run rates lower.

Low demand and oversupply has also impacted base oil pricing dynamics. Hay indicated that base oil demand was down 40%-60% in April and May. Because of this, “base oil pricing of course became pressured as the [low] demand for fuels dragged crude futures to historic lows and VGO along with it. U.S. suppliers then dropped their posted prices by $0.70 up to $1 per gallon.”

Hay reported that U.S. domestic base oil prices slid 24% for Group I, 38% for Group II and 16% for Group III compared to pre-pandemic levels.

Doing Their Best

Refiners are using various tools and strategies to pull back on their run rates. “Refineries have made tough choices regarding how best to reduce product output,” Claxton said. “A straightforward crude reduction might not be adequate, since refineries cannot slow down to, say, 25% or 50% of total capacity due to equipment turndown design limitations.

“Planned downtime schedules were accelerated into earlier months but were limited by the availability of materials needed during the turnarounds to perform necessary repairs. Extended turnarounds have also become common” in the COVID-19 era, she noted.

The integration of base oil plants into larger refineries presents another challenge when fuel product demand is much higher than base oil demand. This problem can be managed, though. “With planning and coordination, the base oil units can often be taken offline while the rest of the refinery continues to operate,” Claxton explained.

On the other hand, base oil units need the fuels refining infrastructure to continue operation. For example, said Claxton, when crude units and portions of downstream fuels cracking units are operating at reduced rates or are taken offline completely for a turnaround, the integrated base oil units are also required to slow or shut down because the base oil facility no longer has access to the feedstocks it needs to operate. This occurs independently of base oil demand. This has been the situation recently, and contributed to a rebound in base oil prices in the second half of 2020.

“Similarly, if a fuels refining unit or hydrogen generation unit is shut down for maintenance, the base oil units requiring significant amounts of hydrogen, such as hydrocrackers and hydrodewaxers, must also be taken offline, which impacts Group II but not Group I base oil facilities,” Claxton explained.

Another refining integration issue arises because demand for fuels products is fairly straightforward and transparent, while base oil demand often hides behind the longer supply chains in the various base oil demand sectors. “For instance, a very short time lag exists between the airline industry grounding planes and refinery jet fuel tanks becoming full,” said Claxton. “The link is very clear, and required throughput adjustments are quickly evident. Base oils are not in and of themselves a finished product, and supply chain issues delay and often camouflage shifts in base oil demand.”

She continued, “Throughout the pandemic, each base oil demand sector has seen differing amounts of curtailment, leading to less immediate and less obvious needs for refining throughput adjustment on base oil units. There is a time lag when demand falls for finished lubricants, and the refinery base oil supply chain supporting finished lubricant blend plants needs to adjust.”

Is Stand-alone Standing Better?

Globally, there are one large and five smaller virgin base oil facilities that are not integrated into a larger refinery, one of which is in North America, said Claxton. Petro-Canada’s 14,700 barrels per day API Group II and III plant in Mississauga, Ontario, is dependent upon feedstock shipped from across the Atlantic. The five smaller refineries, which are in Asia, the Middle East and Europe, are co-located at or near a large refinery owned by a separate entity and receive feedstock by pipeline or rail. During normal operating times, this is not an issue for the small plants with local feeds, but Petro-Canada could be at a significant cost disadvantage because of shipping.

However, the pandemic could potentially have less of a negative effect on non-integrated base oil producers, as “having the flexibility to continue running at required throughputs independent of a fuels refining slowdown would be advantageous during the economic downturn triggered by the COVID-19 pandemic,” Claxton explained.

On the other hand, said Claxton, refineries providing feedstocks to these standalone base oil plants may also be curtailed as part of fuels refining slowdowns. This could jeopardize the availability of third-party feedstocks on which the stand-alone facilities depend, subjecting them to the same problems as integrated base oil plants.

Sydney Moore is assistant editor for Lubes’n’Greases magazine. Contact her at Sydney@LubesnGreases.com.