Best Practices for Flushing Lube Blending Lines

Lubricant blending processes produce a surprisingly small amount of waste. “Due to the cost of the raw materials—both additives and base oils—very little in the manufacturing process creates waste,” explained David Wright, director general for the United Kingdom Lubricants Association.

However, most companies blend many different types of lubricant products at their facilities, and it is critical to quality control that residual product from one formulation is not allowed to mix with another.

Since it is not practical—nor is it really possible—to have separate manufacturing systems for each and every product that a lube manufacturer blends, “between blended batches it is usual for blending vessels to be flushed through to ensure no cross-contamination between products as manufacturing switches from automotive to hydraulic oils, for example,” said Wright.

Large lubricant blenders, such as Shell Lubricants, blend hundreds of different products, and those companies’ blending infrastructure must be shared amongst the various products, said Paul Stach, supply chain development manager, Americas, for Shell Lubricants. Because of this, blending vessels must often be cleaned between products to eliminate the threat of wasting usable product and cross-contamination.

Lubes’n’Greases columnist and industry consultant Steve Swedberg agreed, explaining that “Any time an oil is blended, there is always some leftover oil that must be handled.”

After one product has been blended, Stach said, “that pipe is still full of fluid, and you have to push that fluid back into the tank [before blending another]. These pipes could be hundreds of feet long, so that could be 500 or 600 gallons [of product] that you don’t want to waste or put in the wrong container.”

Recover

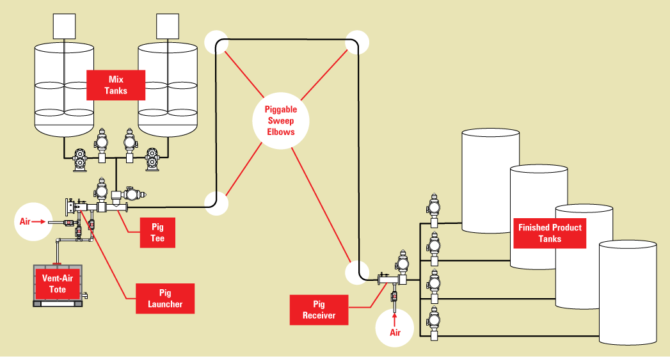

There are a few common methods of cleaning out lube blending systems to prepare for making a different product, one of which involves the use of a pigging system. According to Stach, use of “a pigging system would be more associated with product families [similarly formulated products] where there is some compatibility between products.”

In the pigging process, a plastic or rubber plug—called a pig—is placed inside of the pipe that needs to be cleaned. Then compressed air is pumped through the pipe in order to push the pig down the line and push out the remnants of the previously blended product.

According to Ashley Murray, sales coordinator and director of marketing at Tomball, Texas-based Pigs Unlimited International, process pigs, which can be used for packing, storage, cleaning, loading and unloading of lines, are helpful to the flushing

process because “the unique designs of the process pigs minimize bypass, thereby minimizing cross-contamination and normally wasted product. The flexibility of the pigs helps navigate the bends and fittings often found in these [lubricant manufacturing] lines.”

Pigs can recover most, if not all, usable residual product, asserted Murray. This is ultimately quite economical, as the “savings will become significant over time due to the reduction of waste, improved efficiency and environmental sustainability,” she said.

Because production lines come in various sizes, the pigs are also available in customized sizes to ensure a tight seal. Process pigs can range in price but typically cost about $100 to $400 per pig, and the average lifespan of the pigs varies. “The pig must create a seal to move and push the products in the line. Once this seal is worn, the pig must be replaced. The longevity of the pigs depends on how long the run is, how often the pig is used and the material in the line, to name a few factors,” said Murray.

Reduce

Another method to flush pipes involves the use of flushing oil to rinse previously blended products out of blending vessels and filling lines.

However, Stach asserted that “The first thing we do is try to minimize any flush at all because that could be construed or back-calculated as waste and extra expenses. But when we do have to use it, we use it for quality purposes to make sure our blending systems and our packaging lines are clean. That way, when we schedule the next production, there is no cross-contamination.”

Stach explained that Shell does everything possible to minimize flush by creating a production schedule that groups “product families” that are compatible with each other. “You could actually prevent any flush by having that grouping and having a planning team that sequentially puts products in an order in which there’s compatibility all the way through. We also use a lot of dedicated tanks and dedicated systems, so that prevents any cross-contamination.”

|

“The first thing we do is try to minimize any flush at all.”

– Paul Stach, Shell Lubricants

|

Stach described the process used to prepare vessels for blending:

“The flushing process is pretty simple. We have dozens of types of base oil. We try to use one that’s appropriate for cleaning. I think different scenarios could open up different opportunities for which type of base oil you use; you want to use one that will get the job done but is also not your most expensive base oil out there. We’ll pipe base oil to the tank that needs to be rinsed, and then we’ll put it on some cycle where you’re just circulating this base oil, basically flushing and cleaning the tank out.”

Swedberg added that “how the oil is blended determines how the system is flushed. If you blend in a small vessel, the system is washed down with a small amount of either base oil or blended oil that will be the next oil to be blended in that vessel.” For example, a hydraulic oil may be blended, and the next product to go in the vessel will be gear oil. In this case, the vessel could be flushed with gear oil—about 25 to 50 gallons for a 500 gallon vessel.

For an inline blender, which is made up of several component tanks with meters to inject the right percentages of components into an oil stream, blending of the same oil in a different viscosity grade can be started, and the small amount of the previous product in the lines is mixed into the new oil, Swedberg continued. This may make up about 50 to 100 gallons in a several thousand-gallon storage tank. “The only time a flush occurs is when a lower-viscosity oil is to be run after a higher viscosity oil,” he noted.

Oftentimes, properly flushing a blending vessel becomes part of the blender’s quality control process. “There are a lot of reasons that we put quality programs in place,” Stach explained. “Our customers require it, and they have certain specifications.” (For more about lubricant quality, see Steve Swedberg’s “Automotive” column on Page 18.)

Because of this, Stach emphasized that in order to ensure a high-quality blended product, Shell tests the flushing oil that comes out of the blending vessel in a lab three or four times to make sure that the blending vessel or packaging line is clean. Blending of the next product only begins when the lab gives the go-ahead.

“We try to minimize whatever risk there is with contamination. It’s a game-time decision with the lab and the plants. This is where they might have some latitude. It has everything to do with the customer and the quality and our certifications. We follow all those rules and standards,” he assured.

Reuse

Once a blending vessel is clean, the oil used to flush it is often stored in tanks until it can be used as flushing oil again. When base oil can no longer be reused as flushing oil, it is still a sellable product, said Stach. “It can get downgraded very easily and be turned into something like chain saw fluid, which doesn’t really have any true specifications it must meet.”

Overall, most companies will do all they can to minimize the amount of waste produced by the lube blending process. “Being good commercial people, if there’s an opportunity to reuse [flushing oil], then we will reuse it,” said Stach. “If not, then it could be liquidated.”

When looking to sell used flushing oil, Stach asserted that “there are some folks out there who will buy [the used flushing oil], but it’s not something that we do to make any money. It’s something we do out of necessity to keep our quality and our integrity.”

Importantly, Stach told Lubes’n’Greases that Shell does not use flushing oil in any of its formulated products.

Sydney Moore is assistant editor for Lubes’n’Greases magazine. Contact her at Sydney@LubesnGreases.com.