Specification development is tricky. Developing even one benchmark requires years of testing and countless hours of collaboration, all in the name of ensuring each bottle of motor oil that hits the shelves meets the requirements of modern-day engines. But tests themselves can fail, and what follows is rarely an easy process.

On February 27 this year, the American Petroleum Institute announced that the ASTM D6709 Sequence VIII test was being put on hold. It is used to prove that a formulation can meet standards for ILSAC GF-6A and API SP, SN, SM, SL or SJ.

“ASTM D02.B0.01 Sequence VIII Surveillance Panel has reported that the [test] is currently out of control and not available at independent laboratories,” explained Jeffrey Harmening, senior manager for the Engine Oil Licensing and Certification System, Diesel Exhaust Fluid Certification and Motor Oil Matters programs with the American Petroleum Institute.

This means that any lubricant blender seeking licensing for a new formulation is currently unable to run the test. When that happens, API invokes provisional licensing, allowing a formulation to be temporarily approved for market even if it cannot pass the test because the test is unavailable.

“The test is designed to determine weight loss in bearings due to corrosion,” said Pat Lang, manager of crankcase lubricant testing at San Antonio-based Southwest Research Institute. “As a result of oil degradation, the acidity of that oil can increase. So if it does increase, then you can have chemical etching of that bearing that may compromise the ability to maintain proper bearing function.”

The Southwest Research Institute is one of two labs that run benchmark tests for lubricant formulations.

To determine if an oil can pass the test, the lab weighs the bearings and then runs the oil through a 40-hour test. After that test, they weigh the bearings again to determine weight loss.

If there is an extreme change in weight, it would suggest that the oil being tested is of a corrosive nature. “That’s kind of a red flag,” said Lang, who is also the chairman of the Sequence VIII Surveillance Panel. “The problem with that is that as your bearings corrode in an engine, you end up with material being removed, and you can end up with more clearance, which is critical in terms of maintaining the oil film between those two components.”

As the clearance increases, there is a drop in oil pressure, which can lead to mechanical interaction between the bearing and the crankshaft journal.

The Sequence VIII is an old test. Modern bearings are typically made with aluminum. But older configurations use copper and lead, which still need protection in the field.

As Lang put it: “It just works, so you might as well keep it.”

Updating the test is not simple, though. Test development is expensive and takes years. The test has been slated to be replaced before, but it remains, since there is no viable alternative in place.

Original equipment manufacturers “are focused on the newer hardware but recognize the older hardware still needs protection,” Lang said. “They’ve got their new technology engines out there that they need to protect. This bearing weight loss is a concern, but we’ve got a tool that gauges it.”

The industry is beginning to talk about the introduction of ILSAC GF-7, which could potentially mean a new test, but nothing is set in stone yet. Lang thinks that an update for GF-8 is more likely. “I think that the Sequence VIII is going to remain in GF-7, but I think for GF-8 it’s going to be replaced probably with a bench test—not an engine test, but a bench test.”

Acceptable Limits

ASTM D6709 Sequence VIII measures weight loss in milligrams. Any formulation—or a candidate oil—that a lubricant blender submits for testing must cause no more than a 26-mg bearing weight loss after the 40-hour test. Typical candidate tests are much lower than 26 mg of loss, but as long as it’s lower than 26 the candidate oil will pass. It is a test with one of the highest pass rates of all the tests required for the current category.

How was the 26-mg threshold decided? While inferences can be made, no one quite knows.

“This test has been around for 50-plus years in different flavors, if you will,” Lang explained. “So in the early days of this, the threshold of passing/failing was likely correlated to a problem that was being observed in the field.”

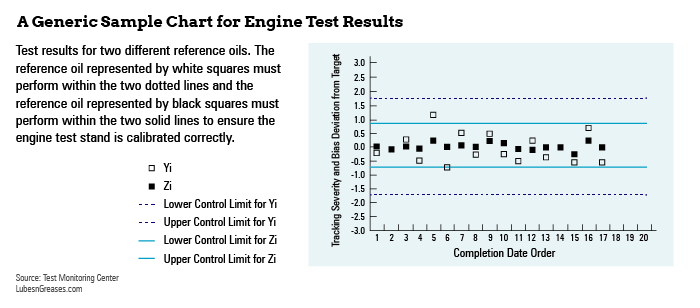

A reference oil, which is a formulation of known performance that the laboratories use to calibrate the test, is periodically used to ensure the test is running correctly. But it has stricter acceptable limits. In this case, the reference oil testing for ASTM D6709 Sequence VIII, called 1006-2, must cause a bearing weight loss of no less than 9.2 mg, and no more than 25.7 mg. This oil is of an “older vintage,” Lang said, since the test is older, meaning it is not entirely representative of oils that exist in the field today.

The current issue is that the reference oil is testing higher than the acceptable limit.

A reference oil not running correctly can happen without a test becoming unavailable. Sometimes the issue can be solved before such a measure must be taken.

With this test, however, both Southwest Research Institute and Intertek, the only two labs that run it at this time, were seeing similar failed results: the reference oil was causing a bearing weight loss over the allowable upper limit of 25.7 mg for this oil. (Actual weight loss ranged from 28 mg to 35 mg.)

Failed results can fall under the category of mild or severe. These results are considered severe.

What’s Causing the Test Failure?

The labs are working together to solve the issue, running tests at their own cost. “We tried to screen out a few items that we thought might be the reason for the problem and were not successful,” Lang said. At that point, the decision was made to advise API that the test was unavailable. As a result, API invoked provisional licensing.

One potential cause of the failure may have been that the current batch of bearings had degraded. Bearings can age and give an unusual test result. But a batch of newer bearings were tried and gave the same severe results, ruling that out as the problem.

Another common item used between the labs is fuel. This is not fuel you would pump into your car at the gas station, but rather it is from a supplier where special provisions are taken to provide a consistent fuel from batch to batch to help minimize variations that could potentially affect test results. The labs tested whether the current batch of fuel was causing the issue by going back to an older batch and running the tests. They still saw failing results. Other parts of the engine were checked to ensure they were in order.

Each lab has two test cells, and there can be biases between each test cell, even if they run the exact same procedure.

“Stand A versus Stand B might have a bias one way or another,” Lang explained. “So now, two test cells at two different laboratories are giving us the same severe results. So statistically that tells us a lot, right? So not only does it take out the laboratory, but it takes out the test stand.” That also eliminates the engine as the problem, since each test stand uses a different engine.

“We’re actually circling back now and looking a little bit deeper at all those, because we haven’t been able to nail it down,” Lang said. “But one of the things that we learn over and over in standardized lubricant testing is that as an engineer you hope to find the smoking gun, right? Or I can definitively put my finger on it. It’s obvious, right? But too many times we look for something obvious and we overlook some subtlety. As a result, we are circling back and making sure we didn’t miss anything.”

Calibration Frequency

If the problem were to be found today, the test could be calibrated in a couple of weeks, since it is only a 40-hour test.

When ASTM D6709 Sequence VIII is running as intended, a test stand-engine combination is calibrated after conducting 15 candidate tests or every six months, whichever comes first. In a slower year, a stand will typically be calibrated twice, but a particularly busy year may result in three or four calibrations. Southwest Research Institute will typically run about 100 tests per year.

Compared to other tests, the Sequence VIII test is run less often. Some tests require more routine calibration because they can run between 250 to 300 tests in a year within multiple labs. However, these numbers can vary for every test from year to year.

Provisional Licensing

API invoked provisional licensing so formulations yet to undergo the test can still temporarily qualify as compliant. New lubricants can still be licensed without this test for as long as it is unavailable. To get a provisional license, companies “must be able to provide data that support the performance of the candidate formulation in the Sequence VIII test,” API stated. A company would be required to provide some manner of engine test data for their formulation that assures that their product would pass the test.

“Without meeting this technical hurdle, API will not approve the provisional license,” Harmening said.

Once provisional licensing ends, any formulation under that designation must complete the test within six months to pass Sequence VIII and gain approval from API.

If a provisionally licensed formulation does not pass the test, the licensee must inform API and take any corrective action API deems necessary, including product recall.

ASTM D6709 Sequence VIII became unavailable once before. In 2016, API halted the test and issued provisional licensing due to a shortage in connecting rod bearings. In that instance, provisional licensing was invoked from mid-April to mid-August, Harmening said.

“We’re very confident that we can get this test back online soon,” Lang said. “We’ll figure it out. We always do.”

Will Beverina is assistant editor for Lubes’n’Greases. Contact him at Will@LubesnGreases.com