Trevor Gauntlett explores how one of the pivotal moments in the life of the director of the Manhattan Project’s Los Alamos Laboratory had positive consequences for the lubricants and additives industry.

One of the most significant moments in the life of J. Robert Oppenheimer is depicted in the summer 2023 blockbuster film with a reference to “my friend at Shell.” This friend is the British physicist George Charles Eltenton, described in many American publications as a Russian spy.

It should be noted, though, that Eltenton always denied all allegations of espionage and never faced any charges for the alleged offense. He did, however, work for Shell, and the cascade of events associated with Oppenheimer led Eltenton to make some highly relevant interventions in the technology of lubricants.

Eltenton: “My Friend at Shell”

Politically, Eltenton was an anti-fascist, and he spent five years in Leningrad with a wife who so liked the city and Soviet society that she wrote a children’s booklet in 1947 and entitled her memoir “Laughter in Leningrad.” When Eltenton relocated to California, he moved in Russian-speaking circles. This was especially apparent as his daughter—eventually a ballerina of some note with the Sadler’s Wells Company in London, England—was learning ballet from Russian teachers in San Francisco.

It is also a fact that Eltenton was asked by Peter Ivanov—the secretary of the Soviet Consulate in San Francisco and someone who was implicated several times in espionage—if he knew anyone working at the Los Alamos Radiation Laboratory and if he could gain information for the Soviet Union, which was an ally in World War II. Eltenton offered to ask Oppenheimer’s close friend, Haakon Chevalier, who then asked Oppenheimer at a party in either late 1942 or early 1943.

Oppenheimer said “no,” but his loyalty to Chevalier led him to first not report the approach. Later, he changed his story, which led to severe problems for both men when the United States House of Representatives Un-American Activities Committee (HUAC) began investigating Oppenheimer in 1946.

Coincidentally, though, this was also the point at which Eltenton’s life took a sharp turn that led to some highly relevant research work in lubricants.

A Life-Changing Move

Eltenton had been employed since 1938 by the Shell Development Company (SDC) in Emeryville, California, as an expert in spectroscopy. His work during that time covered novel methods for non-invasive pipeline inspection using variations in magnetic fields to detect corrosion. Patents on the analysis of mixtures (and their link to process control) included the development of colorimetry as a tool for monitoring liquid mixtures under flow, refractive index measurement of hydrocarbon blends such as fuels, and infrared spectroscopy on gas mixtures. The latter was published after he left the U.S.

Eltenton’s name came into the public realm in late October 1947 when Chevalier named him in a testimony before HUAC, which was investigating Soviet attempts to obtain information on the activities at Los Alamos with respect to the Manhattan Project. The New York Times reported that he had resigned his position with SDC on October 10, with the clear implication drawn by many that he had “cut and run” before the HUAC inquiry reached him.

As Eltenton was interviewed by the Federal Bureau of Investigation with respect to the “Chevalier incident” in June 1946, it is possible that he initiated a request to move shortly afterward. For most of the 20th Century, almost all Shell staff transferring across the Atlantic were required to resign from one company and join the other. In a statement to MI5 in November 1947, Eltenton stated that he believed “that the matter was buried by the FBI as ‘inconsequential,’” implying that the HUAC investigation did not influence his decision to ask to return to the U.K.

He stated that he had been allowed to leave the country on vacation after the FBI interview and that he “had no difficulty in leaving the country for [his] present assignment.”

According to United Kingdom police records, Eltenton’s family had arrived in England in September 1947 and been placed in an hotel at Shell’s expense close to what would become his new place of work.

Eltenton took up a position with Shell Research Limited at Thornton Research Centre—Shell’s then global research center for fuels, lubricants, greases and other such research as metallurgy and materials science. However, Thornton had been a significant part of the British war effort, developing pour point depressants and other fuel and lubricants additives that allowed the allies to fly their airplanes (particularly the Hurricane fighter and the Lancaster bomber) higher and for longer periods of time than the Germans could.

With such a wealth of application experience, Thornton was preparing to begin new government-sponsored and classified research in early 1948. This alarmed the American authorities. It also alarmed SDC¸ as they had concerns that the presence of someone deemed un-American would deny them access to Thornton’s world-leading research on fuels and lubricants.

While external pressure from the British government to move Eltenton away from Thornton had been vigorously opposed by Brigadier Ralph Alger Bagnold—an accomplished rheologist and director of Shell Research Ltd.—pressure from SDC resulted in Eltenton’s transfer to the Shell Chemicals Research Laboratory at the adjacent Stanlow Refinery about a year after he began at Thornton.

This move ensured that Eltenton had no chance of working on classified research and coincided with the reduction in interest in his activities. In fact, his name re-emerged in 1954 when Oppenheimer was the focus of a security hearing by the U.S. Atomic Energy Commission and later whenever a book, television series or film was produced about Oppenheimer.

Applied Research

While Eltenton had been recruited to Thornton as a spectroscopist, the transfer to Stanlow meant that he was immediately immersed in production-related research. His first patents from the period covered the recovery of spent sulfuric acid from the sulfonation of olefins and alcohols to produce surfactants.

Subsequent patents were under the auspices of Shell Research Limited, which could imply a return to Thornton. However, Shell does not share employee histories, the U.K. authorities lost interest in Eltenton after 1954, and the one Thornton employee Lubes’n’Greases managed to find who was a contemporary of Eltenton’s could not remember him, despite being at Thornton from 1948 to 1973. This probably reflected the hierarchy in many British establishments at the time, where the managerial grades only ever had contact with their direct reports, taking tea breaks and lunch in separate places from the technical staff.

During his time at the refinery, Eltenton returned to two previous areas of research: application of novel techniques to process improvement and sulfonation. The former work covered a method of continuously measuring and/or recording the vapor pressure of a stream of liquid, with a particular reference to gasoline.

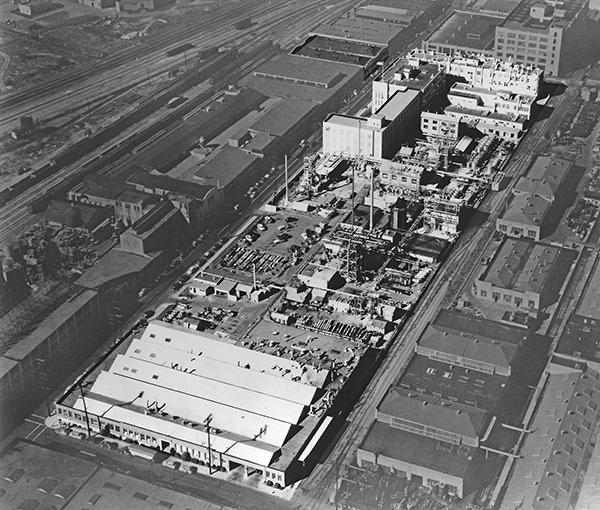

An aerial view of Shell Development Company’s facilities in Emeryville, California.

© Photo courtesy of Emeryville Historical Society

Further work on sulfonation was targeted at the production of natural or petroleum sulfonates, which were the mainstay of metalworking and transmission fluids for much of the following 50 years. This work would have been the domain of the oil refinery as a supplier into the lubricants market—either to additives suppliers or to lubricants blenders. Toward the end of the 20th Century, Shell was the dominant supplier of natural petroleum sulfonates in the West. Eltenton then moved to continuous methods for sulfonating many organic materials, including the alkylated aromatic compounds that are the starting points for the sulfonate detergents used in lubricants today.

Following those forays, Eltenton turned his attention to lubricant detergent manufacture, with the first patent filed in April 1954. Eltenton included in these patents examples of lubricant formulations based on basic calcium naphtha sulfonates and a marine diesel oil solution of basic magnesium naphthenates. Much of the focus was on alkyl sulfonate and alkyl salicylate manufacture. While the former was important—sulfonate detergent manufacture is a highly competitive business—the latter was Shell’s unique chemistry, which became the core chemistry for its automotive and marine lubricants for the next 40 years. The technology then transferred to Infineum upon its formation.

The methods in Eltenton’s patents claimed to produce detergents with a higher base number and alkali reserve than the established methods. They were also said to result in a much better distribution of detergent micelle sizes, avoiding agglomeration into very large micelles that cause haze. A narrow distribution of micelle sizes also leads to better retention of alkalinity reserve as the lubricant ages. This was not mentioned in Eltenton’s patents, although it is accepted by some as common knowledge.

His final forays with possible application in lubricants focused on separations, rather than the mixing process he had monitored early in his career. These included a process that could be used to concentrate polymers, such as those used as viscosity modifiers. In some of these patents an example is given of concentrating a sodium alkylbenzene sulfonate, a precursor to lubricants detergents and an example of a synthetic sulfonate, which eventually superseded the natural sulfonates mentioned above.

A Lasting Legacy

An incident with such sufficient resonance that a smash hit feature film was released over 80 years later almost certainly created some ripples in the lubricants field. We will probably never know whether Eltenton really was a Soviet spy, but we can appreciate that his probably-enforced move back to the U.K. resulted in his participation in important work that facilitated the development of products that had an impact at the time as well as lubricant detergents that are still in use today.

Trevor Gauntlett has more than 25 years’ experience in blue chip chemicals and oil companies, including 18 years as the technical expert on Shell’s Lubricants Additives procurement team. He can be contacted at trevor@gauntlettconsulting.co.uk