Last year, governments around the globe scrambled to dodge the economic effects of stay-at-home orders, increased unemployment, widened income gaps and other punches thrown by the coronavirus pandemic. Unfortunately, many did take hits during their ongoing match with the pandemic. Such is the story in much of Latin America.

According to a presentation given by John Price, managing director of Americas Market Intelligence, during the ICIS Pan-American Base Oils & Lubricants Virtual Conference in December, Latin America has been hurt more than many regions. “We took a look at Latin America as a region versus other major regions of the world and determined that Latin America was unusually vulnerable to this pandemic, both as a healthcare crisis as well as economically,” he said.

What has made Latin America so susceptible? Price explained that “economically, it does not have the luxury of printing money to stimulate monetary growth without being punished by the international debt ratings agencies. So that limited the responses that Latin America could muster.”

He also cited that on average 60% of Latin America’s working population is employed informally, meaning that a relatively small percentage of the population could realistically move their work to their homes. “The lockdown measures, which were the only policies they could pursue, were going to have a devastating impact,” he said.

While some countries in the region such as Peru were able to more or less control the spread of the virus within their borders, Price asserted that other countries “never really stood a chance.” These include Brazil and Mexico, which are Latin America’s two largest lubricant markets. “Confusing messaging coming out of different levels of government led to a disunited approach to lockdown and other measures. The COVID pandemic essentially got away from leaders very quickly.”

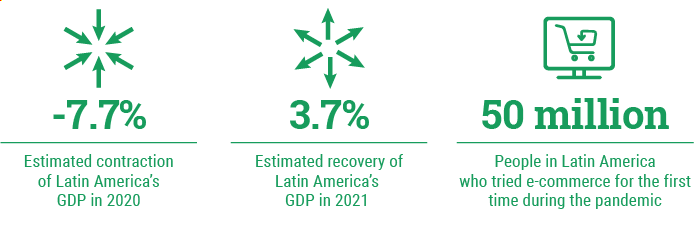

Price predicted that the region’s gross domestic product will take longer to recover in dollar terms to 2019 levels than any other region. The United Nations’ Economic Commission for Latin America and the Caribbean estimated that the region’s GDP fell by 7.7% in 2020 and will rebound by about 3.7% in 2021.

“What we saw very quickly in March and April was a huge exodus of capital from [Latin American] markets to safer-haven assets in the United States and elsewhere,” Price explained. “You not only have negative [GDP] growth in these countries, but you have depreciated currency. So when we measure the GDP of Latin America in dollars, we see that 2020 has lost one-fifth of its value versus 2019.”

However, there is still optimism in the region. In a survey administered by Americas Market Intelligence during a September webinar, attendees from the region were asked what kind of growth they anticipated in 2021 versus 2020. “Close to 90% of them answered that they anticipated positive growth, and on average that growth was about 12%. So that’s certainly a positive sign that rebound is ahead,” Price said.

Furthermore, the pandemic seems to have spurred at least one positive trend in the region. “The exercise of putting everyone under quarantine forced people who up until now had not engaged in digital commerce to suddenly become engaged, whether it was to watch a Netflix film or order groceries,” said Price. “Fifty million people in Latin America tried e-commerce for the first time under COVID. This is going to have an impact even in lubricants.”

Lubricants have largely been distributed through traditional sales channels in Latin America, and there is not a large do-it-yourself market there, according to Price. However, with the move to e-commerce in the region, “there is definitely a shift, even within the lubricants space, to more digital commerce,” he said. “Even small businesses that purchase their lubricants from, say, traveling salesmen that go around to small shops will be buying more and more [business-to-business] online.”

Price concluded that “COVID in Latin America has impacted some industries much more than others. So tourism, aviation, transportation and new car purchases all suffered dramatically under COVID. At the same time, e-commerce has done really well. We see that some of the traditional segments into which lubricants are sold are definitely taking a hit, whereas last-mile delivery, which has increased several-fold in Latin America, will create new demand for lubricants.”

Smaller but Better

According to estimates by the International Monetary Fund, Mexico’s GDP in 2020 shrank around 8.5%.

On the tails of a momentous contraction in the country’s economy, car sales also saw record decreases in 2020. According to Mexico’s national institute of statistics and geography, known as INEGI, there were over 1.3 million light vehicles sold in Mexico in 2019. That figure dropped by nearly 28% in 2020, with just 949,353 vehicles sold.

With automotive lubricants accounting for 80% of finished lube demand in the country, base oil demand also seems to have slipped. For example, Mexican base oil imports from the U.S.—a major base oil trading partner—dropped about 16% from 2019 to 2020, according to U.S. Energy Information Administration data. However, this could be attributed partly to tight supply conditions in the U.S.

Although it was hit particularly hard by the pandemic in 2020, the country’s new lubricant quality standard, NOM 116-SCFI-2018, was officially implemented on schedule on June 16, 2020, in hopes of formalizing the lubricants industry within the country. It defines test methods and implements audits, controls, labeling requirements and document review for heavy-duty and passenger car motor oils. The standard was designed to be similar to the American Petroleum Institute’s specifications and utilizes ASTM test methods, according to Areli Velazquez, research and development chief for Lubricantes de Americas S.A., who also spoke during the virtual event.

Oils manufactured or imported into Mexico must be licensed by API, the European Automobile Manufacturers Association or an original equipment manufacturer, meet all labeling requirements and be accompanied by a “manufacturer responsible letter.” Alternatively, products can pass a slate of tests verifying performance. Certificates of compliance are valid for three years.

As of June 16 this year, the standard bans manufacturing of obsolete heavy-duty engine oil categories API CF, CF-2, CF-4 and CG-4. Such oils can no longer be marketed in Mexico after June 16, 2023.

Is Brazil Bouncing Back?

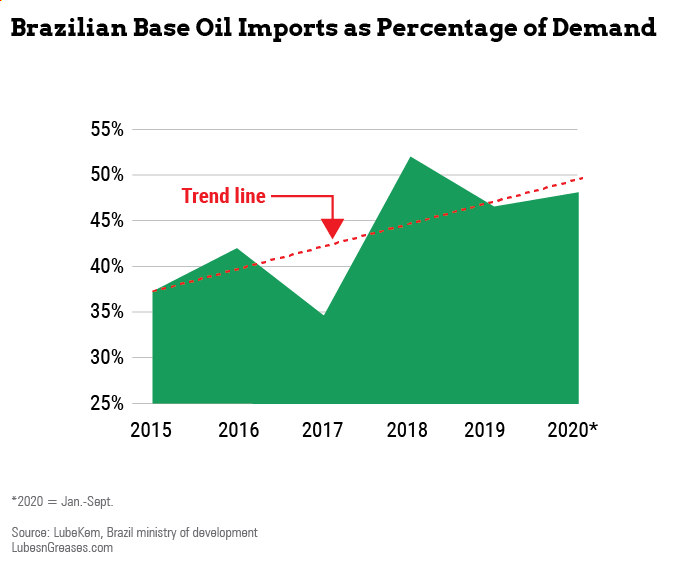

In another presentation, Claudio Silva, director of Sao Paolo-based consulting firm LubeKem, explained that although Brazil has a number of domestic base oil plants, imports poured into the country in 2020 and will most likely continue to do so well into the future. In fact, last year imports satisfied nearly 50 percent of total base oil demand in the country, said Silva. “It’s a really big number, and it’s expected to increase.”

This projection is supported by base oil import figures from Brazil’s National Agency of Petroleum, Natural Gas and Biofuels. The country imported a total of 766,000 tons of base oil last year, an increase of 12% from 2019. In December alone, imports reached 73,000 tons, up 7% from the same month the year prior.

Why the jump in imports? According to Silva, one of the most obvious reasons is the decline of domestic base oil production. The country produced 485,000 tons of base stocks in 2020, down 18% from 593,000 tons in 2019, according to government data. Additionally, state-run oil company Petrobras, the largest base oil producer in the country, has steadily decreased its output for the past several years. Silva predicted that production will dwindle even further because of slowing operations at Reduc, Petrobras’ main base oil refinery in Duque de Caxias.

Petrobras’ base oil production at Reduc has been falling year after year, from about 12,000 barrels per day in 2013 to around 7,000 b/d this year, or about a 40% reduction, Silva observed. The plant currently has capacity to produce 11,200 b/d of API Group I base oils per year, according to the 2020 Lubes’n’Greases Guide to Global Base Oil Refining.

As a result of this decreased production, Silva estimated that the country’s base oil imports are likely to exceed 700,000 tons per year for years to come. “In my opinion, this is one of the biggest short- and mid-term challenges for lubricant blenders in Brazil, mainly for small and mid-sized buyers,” he cautioned.

Specifically, the reduced base oil production in the country has inevitably affected pricing dynamics. Because Brazil is importing so much of its base oil, it has become susceptible to price fluctuations in other regions of the world. For instance, U.S. refiners—which supply Brazil with most of its base oil imports, particularly Group II—upped prices in late August after supply-demand balances tightened as a result of reduced operating rates as well as production outages spurred by a number of hurricanes on the Gulf Coast.

Petrobras’ price increases closely followed those in the U.S. and even slightly exceeded the markups for Group I and Group II in the U.S. When paired with the shortage of supply due to reduced production at Reduc, blenders in Brazil were forced to up their spending on base oils.

Furthermore, Petrobras announced in 2019 that it had plans to sell off eight of its refineries, a few of which include base oil plants. It is almost certain that the sales of Petrobras’ Lubrificantes e Derivados do Nordeste naphthenic base oil plant and Refinaria Landulpho Alves Group I plant—which are expected to be finalized this year—will directly affect domestic base oil supply. However, it remains to be seen whether the impact will be positive or negative. According to the Lubes’n’Greases Guide to Global Base Oil Refining, the Lubnor plant has capacity to make 1,290 b/d of naphthenic base oils, while RLAM can make 1,750 b/d of Group I base oils.

There seemed to be a comeback in the summer. July’s 53,000-ton import volume was Brazil’s second-highest last year, and production in September rang in at 49,000 tons, surpassing 2019’s total for the same month by 26%. But by 2020’s last quarter, production hovered between 40,000 tons and 45,000 tons per month, about 15%-25% less than the same months in 2019.

According to Silva, Brazilian finished lubricants demand has been in recovery, even amidst the political and economic uncertainties in the country. After the initial shock of April and May, every month thereafter had seen increased levels of lubricant demand above those in 2019. “This is really good news,” Silva assured.

But even with some recovery in the second half of the year, finished lubricant demand in Brazil was about 6% lower in 2020 than it was predicted to be in pre-pandemic forecasts, said Silva. It also rang in below overall demand levels from 2019.

Gabriela Wheeler and George Gill contributed to this story.

Sydney Moore is assistant editor for Lubes’n’Greases magazine. Contact her at Sydney@LubesnGreases.com.